READY TO PARTY: MUMIA ABU-JAMAL AND THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY |

||||||

| by Todd Steven Burroughs, Ph.D. special to Prof. Kim's News Notes |

|

|||||

Epilogue"THE BARREL OF A GUN:" THE PARTY'S IMPACT ON MUMIA ABU-JAMAL'S TRIAL(An Oral History)By Todd Steven Burroughs [SCENE: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, July 3, 1982. A verdict has been reached in State v. Abu-Jamal. A virtually all-white jury has convicted Mumia Abu-Jamal of the first-degree murder of Philadelphia Police Officer Daniel Faulkner. In response, Mumia Abu-Jamal, 28, has just made a defiant statement to the judge and jury: "On December ninth {1981, the early morning of the Faulkner shooting}, the police attempted to execute me in the street. This trial is a result of their failure to do so…This decision today proves neither my guilt nor my innocence. It proves merely that the system is finished. Babylon is falling!! Long live MOVE!! Long live John Africa!" [And now, we join the sentencing hearing. What will be the sentence: Life imprisonment or death by the electric chair? Our play-by-play commentators have been assembled. A cross-examination of the defendant is already in progress:] JOSEPH McGILL, Prosecuting Attorney: What is the reason you did not stand when Judge Sabo came into the courtroom? ANTHONY E. JACKSON, Defense Attorney: Objection. PHILADELPHIA COMMON PLEAS COURT JUDGE ALBERT F. SABO: Overruled. MUMIA ABU-JAMAL, from 1982: Because Judge Sabo deserves no honor from me or anyone else in this courtroom because he operates—because of the force, not because of right. (STANDS UP) Because he is an executioner. Because he’s a hangman, that’s why. McGILL: You are not an executioner? [Abu-Jamal had no record of violent conduct prior to the Faulkner shooting.] ABU-JAMAL: No. (SITS DOWN) Are you? McGILL: Mr. Jamal, let me ask you if you can recall saying something sometime ago and perhaps it might ring a bell as to whether or not you are an executioner or endorse such actions: "Black brothers and sisters—and organizations—which wouldn’t commit themselves before are relating to us Black people that they are facing—we are facing the reality that the Black Panther Party has been facing, which is--" Now, listen to this quote: You’ve often been quoted saying this: "Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun." Do you remember saying that, sir? ABU-JAMAL: I remember writing that. That’s a quotation from Mao Tse-Tung. McGILL: There is also a quote— ABU-JAMAL: Let me respond, if I may? McGILL: Well, let me ask you a question. ABU-JAMAL: Let me respond fully. I was not finished when you continued. McGILL: All right, continue. ABU-JAMAL: Thank you. McGILL: Continue to respond, then, please, sir. ABU-JAMAL: That was a quotation of the Mao Tse-Tung of the Peoples Republic of China. It’s very clear that political power grows out of the barrel of a gun or else America wouldn’t be here today. It is America who has seized political power from the Indian race—not by God, not by Christianity, not by goodness, but by the barrel of a gun. MICHAEL SCHIFFMANN, Mumia Abu-Jamal Biographer: [T]he fact that this statement referred to the behavior of the police in Chicago and elsewhere [in 1969] and was by no means intended as a political guideline for BPP practices did not deter prosecutor Joseph McGill from first introducing it into the evidence and then, in his summation where he argued for the death penalty, using it to stress the [so-called] violent mentality of the defendant. McGILL: Do you recall making that quote, Mr. Jamal, to Acel Moore [a reporter for The Philadelphia Inquirer]? ABU-JAMAL: I recall quoting Mao Tse-Tung to Acel Moore about 12 to 15 years ago. McGILL: Do you recall saying, "All Power To The People"? Do you recall that? ABU-JAMAL: "All Power To The People"? McGILL: Yes. ABU-JAMAL: Yes. McGILL: Do you believe that your actions as well as your philosophy are consistent with the quote, "Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun"? ABU-JAMAL: I believe that America has proven that quote to be true. McGILL: Do you recall saying that, "The Black Panther Party is an uncompromising Party, it faces reality"? ABU-JAMAL: (NODDING HEAD) Yes. ABU-JAMAL, from 1993, from a Death Row cell: He [McGill] cross-examined me on that article. What you had was the sudden introduction of the Black Panther Party into a case in which it didn’t fit. The political nature is evident. If the jury were not predominately white, middle-class, older, in their fifties; if they were young people, Blacks, Puerto Ricans, who had knowledge of the current contemporary history of Philadelphia, "Black Panther" would have had a different kind of impact. The words "Black Panther" mean different things depending on peoples’ perspective, their history, their political orientation. There is a generation in America for whom the Black Panthers were not a threat but a lift, a sign of hope for a time. For another generation and class in America the Black Panthers were a threat. The prosecutor knew that exceedingly well, because that was used to bring back the death penalty. When it hit the jury it was like a bolt of electricity. ABU-JAMAL, from 1982: Why don’t you let me look at the article so I can look at it in its full context, as long as you’re quoting? [Abu-Jamal reads the article, dated Sunday, Jan. 4, 1970. He identifies a picture of himself and his old identity, "West Cook, Communication Secretary for the Philadelphia Chapter, Black Panther Party." In an attempt to give the jury the full context, he attempts to read the entire article out loud. He reads his quoting of Mao. McGill interrupts.] McGILL: So that is a quote [of yours], isn’t it? ABU-JAMAL: "Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun." McGILL: Mr. Jamal, is that a quote or is it not? ABU-JAMAL: Can I finish reading? McGILL: Well, is it a quote or isn’t it? ABU-JAMAL: Can I finish reading it? McGILL: Well, will you answer the question? ABU-JAMAL: Didn’t I ask if I could read this in its entirety? McGILL: Will you answer the question? Are there quotation marks there? JACKSON: Your honor—your honor—your honor— ABU-JAMAL: Will you stop interrupting me? [Abu-Jamal wanted to represent himself at his trial, and wanted John Africa, the founder of MOVE, to be named his co-counsel. During the trial, Sabo continually refused the second request. After several confrontations with Abu-Jamal over this issue, Sabo eventually withdrew Abu-Jamal’s power to act as his own attorney. Abu-Jamal was not at all happy with Jackson, his court-appointed attorney, and was not afraid to show it. Nevertheless, Jackson continued to defend Abu-Jamal.] JACKSON: He already agreed to let him [Abu-Jamal] read it. May he read it? ABU-JAMAL: If you want to go over it after I finish, that’s okay. McGILL: Would your honor rule? SABO: Let him read it. McGILL: Okay. [Abu-Jamal continued to read the article, written in the aftermath of the FBI’s war on the Party in 1969. At the time of this article’s publication, the blood of Chicago Panther leaders Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, assassinated by authorities, was barely dry; the Inquirer article was published one month to the day of Hampton and Clark’s murder. Moore wrote: "Murders, a calculated design of genocide and a national plot to destroy the Party leadership is what the Panthers and their supporters call a bloody two-year history of police raids and shootouts. The Panthers say 28 Party members have died in police gunfire during that period, {with} two {in the} last month. Police who have had officers killed and wounded by Panther gunfire deny there is a plot. Police have been shot at, they say simply, and they have shot back. Nevertheless, the gun battles and arrest of Panther leaders have convinced the Black Panthers that is it a party under siege."] McGILL: Mr. Jamal, let me ask you again, sir, if I may—If I may ask a question, Judge—was that or was that not a quote you made to Acel Moore? ABU-JAMAL: That was a quote from Mao Tse-Tung. DAVE LINDORFF, Author/Journalist: He [McGill] got more [ammunition] than he needed from the article. All he needed to do now was to get Abu-Jamal on the stand to state that he still held the views that he had expressed—or seemed to have been expressing if taken out of context—in that 12-year-old article. But at that point, Abu-Jamal finally caught on to his plan and refused to play. McGILL: Is that one that you have adopted? ABU-JAMAL: Say again? McGILL: Have you adopted that as your philosophy theory? ABU-JAMAL: No, I have not adopted that. I repeated that. [Shortly after this exchange, Jackson addressed the jury.] JACKSON: Generally speaking, you have heard character witnesses testify on behalf of Mr. Jamal. The Commonwealth has just had Mr. Jamal to read a statement that he had given perhaps 12 years ago, and Mr. Jamal indicated that he was a member of the Black Panther Party. When he further indicated that he was concerned about the Black community—that is not a concern, unfortunately, of a lot of people. By and large the concern, the interest in the Black community is left with those persons who have an interest in the Black community. Black persons. Black persons who are not at all intimidated by what the system has forced upon them…. For some time in the past at least, the white community has simply been afraid of the words "Black Panther." That was seemingly an attitude of the white people. It was almost as if it was [a Black] Ku Klux Klan, [a similar organization of] the Black people. DANIEL R. WILLIAMS, Author/Mumia Abu-Jamal’s lawyer from the 1990s: To many middle-class whites in Philadelphia, Mumia’s involvement in the Black Panther Party was of a piece with his sympathies for MOVE. Media profiles of Mumia lumped MOVE in with his teenage membership in the Black Panther Party, dodging discussion of the details of either organization or of Mumia’s particular involvement in them. It was enough simply to mention the two organizations, allowing them to intersect in the personage of the arrested journalist so as to propagate an alluring portrait of a dangerous Black radical fully capable of killing a soldier of the status quo. JACKSON (continuing his statement to the jury): But what is it? How much do you really know about the Black Panther Party? Simply because they repeat—as Mr. McGill asked Mr. Jamal—simply because they repeat what someone else, Mao Tse-Tung, may have said sometime ago, can we deny that political power in America was the result of a gun? We know that we fought Great Britain. We know that we fought Indians, and we fought and we fought and we fought. And we’re still fighting in this world. Does that in and of itself indicate that Mr. Abu-Jamal is [advocating] violence? I think not, the article went on to state that the [Philadelphia] Black Panther[s], along with Mr. Jamal, fed 80 Black kids daily. Can any of you—and I don’t say this in criticism—but can any of you say that you fed 80 Black kids each day? Those Black kids needed to be fed. So the reality of the Black Panther Party, the reality of Mr. Jamal’s interest, the reality of Mr. Jamal’s activities presented to you now for which you are to judge whether or not this man is to receive the [death] penalty or life imprisonment. [After Jackson was finished, McGill gave his final statement to the jury. He discussed Abu-Jamal’s almost constant defiance during the trial as yet another example of the need for law and order. Faulkner, the slain officer, represented this need, declared McGill. Discussing the defendant’s contempt for his own attorney, the prosecutor said Abu-Jamal saw Jackson as a "traitor" because Jackson was representing and following the law.] McGILL: Again, this is what this is all about, law and order. How do we avoid it if we don’t like it, we don’t just accept it, and we don’t try to change it from within, we just rebel against it. And maybe that was the siege all the way back then with political power, power growing out of the barrel of a gun. No matter who said it, when you do say it and when you feel it, and particularly in the area when you’re talking about police and cops and so forth, even back then, this is not something that happened over night.WILLIAMS: McGill, the one who first gave voice to the hard-line anti-Mumia perspective [that exists today], had no interest in learning about Mumia’s life to gain insight into his political and moral beliefs. He simply extracted from a 1970 newspaper article a Mao quote that was fashionable among Black Panther members at the time and wove a story around it. Mumia’s affiliation with the Black Panther Party and his attraction to MOVE symbolized his renunciation of law and order, which is nothing more than a lazy slogan for preserving the status quo and all of the values that support it.Whether Mumia killed Officer Faulkner or not became secondary inasmuch as it was taken as a starting point for McGill. The trial, from the prosecution’s perspective, was not so much about proving Mumia’s guilt as it was about explaining it. McGill’s success in positing a compelling explanation for the killing—leaving aside whether the explanation was right or wrong—propelled the case toward its ultimate death verdict. That success still drives the anti-Mumia rhetoric….. The Panthers were indeed fond of Mao’s remark that "all political power grows out of the barrel of a gun."Mumia’s early political awareness could not have sidestepped such sloganeering. But it was too much for McGill’s jury, nurtured on network news and sitcoms, to understand that the Panthers in general, and Mumia in particular, embraced Mao’s remark as an observation, a pithy distillation, of European and American history. Mumia tried to explain that point to the jury, but the transmittal of that message, occurring in Judge Sabo’s pressure-cooker courtroom with the fog of death hovering over the proceedings, was lost upon an audience that had already adjudicated Mumia a cold-blooded cop killer.[The jury called for the death penalty. In 1983, Sabo sentenced Abu-Jamal to death by the electric chair.]

|

Table of Contents

|

|||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

||||||

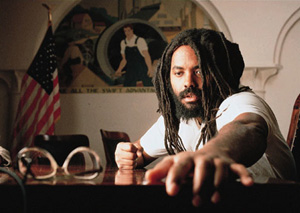

| photo of Mumia Abu Jamal | ||||||

| Copyright © 2004 by Todd Steven Burroughs. Used with permission of the author. | photo of Todd

Steven Burroughs from Research Channel |

|||||