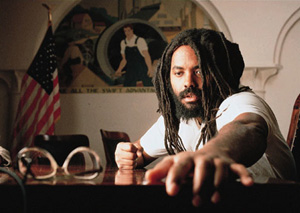

READY TO PARTY: MUMIA ABU-JAMAL AND THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY |

|

| by Todd Steven Burroughs, Ph.D. special to Prof. Kim's News Notes |

|

NOTE: In his new book, "We Want Freedom: A Life In The Black Panther Party" (South End Press), Mumia Abu-Jamal, a Pennsylvania Death Row inmate, remembers his Party days. In this excerpt of "We Want Freedom," he recalls how he and other Black Philadelphia residents formed the city’s BPP branch. – Todd Steven Burroughs FOUNDING THE PHILADELPHIA BPP (PART II)By Mumia Abu-Jamal Once a Black Panther Party chapter was formed, other questions remained. What would the new organization do? How would we let folks know we existed? What would be our focus? These were but some of the challenges facing the group [who] met in by the late spring of 1969. With the renting, repair, cleaning, and painting of the storefront at 1928 West Columbia Avenue, the local Party would have its first formal presence (odd apartments and private homes had sufficed previously), a reliable place where people could contact us. Time seemed to have conspired to await our coming, for the clear air, the bright sky blue, the very essence of the season of new life was upon us. No sooner had we finished painting the walls (Panther powder blue, with black glaze adorning the moldings), affixed a few posters to the walls (Malcolm X, Che Guevara, [BPP Co-founders] Huey [P. Newton] and Bobby [Seale], armed), and used pressure-sensitive letters to inscribe the inside of the fronting glass the black, capital, gold-edged letters: YTRAP REHTNAP KCALB Then people began appearing at our door—the young, the old, and those in the middle, from the cautious to the curious. (For example, students came in, anxious to sell the paper.) What drew all those groups was the bold letters blaring from the window: BLACK PANTHER PARTY (Even the established, like the real estate owner who rented the property to the Party and who owned properties all around the neighborhood, took pains to establish their nationalist credentials. The real estate owner confided to us that he went to the historically Black college, Lincoln University, with the revered Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of the independent West African nation of Ghana.) But to have an office was not enough. The fledging organization had to do something. II AFTER MUCH THOUGHT, and a request from the National Office, the captain ordered us to assemble at the State Building, at Broad and Spring Garden streets near the center of the city, to demonstrate for the freedom of the imprisoned BPP Minister of Defense, Huey P. Newton. The Panther leader was facing murder charges stemming from a car stop and shoot-out in Oakland. The objective was to snag publicity for the Party, and thus to inform the city’s huge Black population of our presence. The date is May 1, 1969, and between 15 to 20 of us are in the full uniform of black berets, black jackets of smooth leather, and black trousers. As we assemble, a rousing chant of "Free Huey!" is raised. Leaflets are distributed to passerby, and we are able to inform some people of our presence and how to contact us. Several of Huey’s articles are read over the megaphone, and before long, we have a somewhat rousing rally on our hands. Some of the excited kids from the nearby Ben Franklin High School cut their classes to attend the rally, and several papers are sold. Captain Reggie reads from Huey’s "In Defense Of Self-Defense," which noted, in part:

Cameras went off like popcorn, but we had no real idea who the mostly white photographers were. We assumed they were the press, but some had the unmistakable air of cops about them. It never dawned on us that some were FBI agents building a file on us. Mostly, it was because, in an age of global revolution, it didn’t seem too extraordinary to be a revolutionary, for didn’t America come into being by way of the American Revolution? Here we were, reading the hard, uncompromising words of the Minister of Defense of the Black Panther Party at the State Building in the heart of the fifth largest city in America, while red-faced, nervous, armed cops stood around on the periphery of our rally. What did we think would happen? We thought, in the amorphous realm of hope, youth and boundless optimism, that revolution was virtually a heartbeat away. III IT WAS FOUR years since Malcolm’s assassination and just over a year since the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. The Vietnam War was flaring up under Nixon’s Vietnaminzation program, and the rising columns of smoke from Black rebellions in Watts, Detroit, Newark and North Philly could still be sensed, their ashen smolding still tasted in the air. Huey was our leader, and we felt, with utter certainty, that he spoke for the vast majority of Black folks. He certainly spoke for us. We loved and revered him and wondered why everybody else didn’t feel the same way. Our job was to make all see this obvious truth. His work moved us all deeply, and we believed we could in turn move the world. This feeling motivated us to sell The Black Panther newspaper with passion and spirit, for Huey himself had written that "a newspaper is the voice of the Party, the voice of the Panther must be heard throughout the land." We struggled daily to make it so. We got up early and didn’t go to sleep until late. For most of us, Party work was all that we did, all day, into the night. Our little branch blossomed into the biggest, most productive chapter in the state and one of the most vigorous in the nation. A year after our rally, our branch sold 10,000 Party newspapers a week and had functioning Party offices in West Philadelphia and Germantown. The Party nationally sold nearly 150,000 papers through direct street sales and paid subscriptions per week. The Party was literally growing by leaps and bounds, both locally and nationally. From our original 15-odd members in May 1969, a year later virtually 10 times that number would call themselves members of the Black Panther Party of Philadelphia. We spoke at anti-war rallies. We attended school meetings. We met with high school students. We met in churches. We worked with gangs and provided transportation to area prisons. Everywhere we went, we brought along the 10-Point Program and Platform of The Black Panther Party as a guideline for our organizing efforts. By any measure, we made an impressive beginning. Copyright © 2004 by Mumia Abu-Jamal. Excerpted from "We Want Freedom: A Life In The Black Panther Party," published by South End Press. Reprinted with permission from South End Press. |

Table of Contents

|

|

|

|

|

|

| photo of Mumia Abu Jamal | |

| photo of Todd

Steven Burroughs

from Research Channel |

|