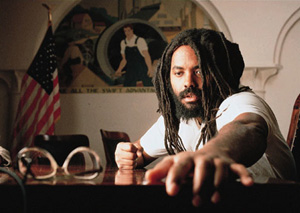

READY TO PARTY: MUMIA ABU-JAMAL AND THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY |

|

| by Todd Steven Burroughs, Ph.D. special to Prof. Kim's News Notes |

|

Prologue:JOINING THE PARTYThe Black Panther Party for Self-Defense may have been a flash in the pan. But that flash provided illumination. Wes Cook, a teenager from Philadelphia who later re-named himself Mumia Abu-Jamal, found friends and an outlet for his energy in the electricity created by the Party. He also found his life’s purpose as a communicator. In short, he found himself. Cook was born in Philadelphia in 1954, the same year the NAACP’s Brown vs. Board school desegregation victory. (As a direct result of the Supreme Court’s action, Mississippi segregationists formed the first White Citizen’s Council.) Meanwhile, three "race men" were making moves that reverberate into the 21st century. The first, a young Muslim minister, was traveling around the nation, speaking at meetings of an organization called the Lost-Found Nation of Islam. (At one of these meetings in 1954, he had "openly spoken against the ‘white devils’ and has encouraged greater hatred on the part of the cult towards the white race," said the man’s FBI file.) Before Cook’s second birthday, another young minister, this one a Christian from Alabama, announced he would help to lead a bus boycott so Blacks would be able to get the respect they earned as paying passengers. The third, a scholar named Ralph Bunche, was appointed as the second-in-command of the United Nations. Like many of the Baby Boom generation, Cook came of age with the Civil Rights and Black Power movements. He was 10 when Philadelphia became one of the first American cities to go up in flames kindled by racial and economic injustice. He was 12 in 1966—a year after the young Muslim minister was killed. Two community college students in Oakland, California, acted on the minister’s suggestion that Blacks form rifle clubs to defend themselves. They wanted to see if revolution could come to the United States the same way it had come in Cuba and several African nations—through a guns’ barrel. The duo, Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton, formed a left-leaning political organization. The new group emphasized community service, political education and self-defense against attacks from Oakland’s racist white police force. Stokely Carmichael, a civil rights activist with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, was organizing an independent political party in Lowndes County, Ala., to test Blacks’ newly won voting power. Seale and Newton asked to adopt the party’s name and symbol, a black panther, as their own. Carmichael and the other SNCC organizers had no complaint. Wes Cook—nicknamed "Scout" or "United Nations" in his neighborhood—wasn’t paying much attention to all this. His world was home and family, spinning stories to his friends and burying himself in the monthly comicbook adventures of Spider-Man. He was called "Scout" because, in the words of his official biographer, Terry Bisson, "he was always on the lookout for something—a construction site, a new candy, a dead dog, a grapevine." Bisson writes that the "United Nations" moniker stuck because Cook would tell the other neighborhood children about "the Quakers who ran the settlement house; about the Jews and their synagogue. He knew all about the Ukrainians who lived a few blocks north, and the Italians who lived to the west and south." Something closer to home helped place him on the Panther’s path. In 1967—following urban insurrections in more than 100 cities, including Detroit and Newark—Student Power and Black Power combined in Philadelphia. That November, Black students in Philadelphia’s public schools held a massive demonstration at the city’s Board of Education. (Bisson writes that Cook went home after only marching a few blocks.) The students wanted a better and Blacker education. Philadelphia Police Commissioner Frank Rizzo took a hard-line approach to the more than 3,000 or so students. Rizzo did his best impersonation of Birmingham’s Eugene "Bull" Connor. "Get their Black asses!" Rizzo shouted to his virtually all-white storm troopers. Nightsticks. Broken bones. Blood. No officers punished. The following year, the young Christian minister from Alabama was killed for attempting to force the United States government to re-commit to the War on Poverty. Many young Blacks wanted to avenge his death. Some did by looting and busting windows in scores of cities. In the aftermath, thousands of young Blacks had another idea: they wanted to join that group of radical cats they had heard about in Oakland. So they set up, or flooded existing, local chapters and branches. They purchased rifles, Black jackets and Black berets. Since Brother Martin’s way didn’t work, they thought, let’s try Brother Malcolm’s. Ungawa. Black Power. A 1968 George Wallace for President rally in Philadelphia. Cook and his friends booed and hissed Wallace and his supporters. Some Wallace supporters decided to respond as a gang. A frantic Cook happily spied a policeman. What happened next Abu-Jamal recalls in his first book, "Live From Death Row": "The cop saw me on the ground being beaten to a pulp, marched over briskly—and kicked me in the face." (Cook’s FBI file, in contrast, stated that Cook struck the officer.) Another not-so-insignificant event happened in Cook’s life that year. He was given a new name by one of his high school teachers, a Kenyan named Timone Ombina. (Later, Cook would add an Arabic surname when his first child, Jamal, was born three years later.) His new name was a royal one to Kenyans, one historically identified with leadership and struggle. Cook took to his nominal rebirth immediately. It coincided with the new identity created by puberty. During this time, he discovered something that galvanized him in all his parts: a weekly tabloid newspaper. Its volatile mixture of newsprint, words, drawings and pictures stirred the Scout and the United Nations within him. The newspaper was The Black Panther. Cook’s life—and, years later, his courtroom struggle to not be put to death—would be defined by the ideas expressed in its contents. His attraction and commitment to the Party was complete. He joined up with some other Black men who could trace their outlines within the Panther’s shadow. The remaining challenge: customizing a West Coast idea for Philly. Cook was turning 15. In transition from boy to man, he had begun an intellectual and activist voyage. By the close of 1970, his adventures would take him to major cities on both American coasts, create lifelong friends and enemies, and plant the seeds of a lifelong vocation. (NEXT: "Do Something, Nigger!") Copyright © 2004 by Todd Steven Burroughs. Used with permission of the author. |

Table of Contents

|

|

|

|

|

| photo of Mumia Abu Jamal | |

| photo of Todd Steven Burroughs

from Research Channel |

|