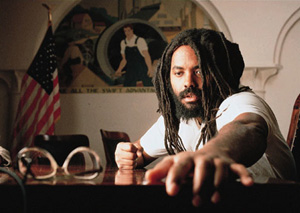

READY TO PARTY: MUMIA ABU-JAMAL AND THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY |

|

| by Todd Steven Burroughs, Ph.D. special to Prof. Kim's News Notes |

|

Part Two:THE PARTY IN PHILADELPHIABy Todd Steven Burroughs Wes Cook, a teenager from Philadelphia who later re-named himself Mumia Abu-Jamal, was in constant motion as a Black Panther Party member. Cook wrote leaflets, press releases and pamphlets for the Party’s Philadelphia branch. He also wrote about Philadelphia Party matters for The Black Panther, the Party’s national newspaper. "I was their Lieutenant of Information," Mumia Abu-Jamal recalled in an interview in "Still Black, Still Strong: Survivors Of The War Against Black Revolutionaries," a small book filled with interviews with Black radical prisoners. "My function was really propaganda, putting out information in support of the Party, and about the situation in Philadelphia." As a Party representative, Cook visited Party offices in Harrisburg, Pittsburgh and other Pennsylvania cities. He spoke at Panther events, such as the Philadelphia commemoration ceremony for Fred Hampton, the 21-year-old Panther leader in Chicago assassinated by that city’s police officers in late 1969. Mark Clark, another Chicago Panther, was also killed during the raid. The young Philadelphia Panther gave interviews to local media. One such interview, published one month to the day after Hampton and Clark’s death, landed Cook on the front page of The Philadelphia Inquirer on Sunday, Jan. 4, 1970. His image—young, Afroed, on the phone, hard at work for Black liberation—would be remembered. (The photo would appear on the cover of his fifth book, "We Want Freedom: A Life In The Black Panther Party.") So would his quoting of Chinese Communist Party Chairman Mao Tse-Tung—the one about how political power gushes out of a gun’s barrel. He also did all the other typical Panther tasks—assisting with the breakfast program, standing guard over the headquarters, working with the other comrades on the various community service programs. In between, there was time for food and sleep, all with his fellow Panthers. In the community of Party chapters and branches, Philadelphia, a branch, made its name through community service, not gun brandishing. The Philadelphia BPP spent most of its time protesting or lobbying for people who either did not know how to, or could not, make local government agencies respond to them. For instance, if city officials wouldn’t take action to fix the constantly backed-up sewers on Columbia Avenue, then the Panthers would block the street until the bureaucracy moved in their direction. And if four Black women were being harassed after moving into an all-white housing development, then the Panthers would stand by those sisters for as many days it took until the mob gave up. And if a young Black man was fatally shot by white highway patrolmen when he and witnesses begged them not to shoot, then Cook would write a 16-page pamphlet about it, and he and the other Panthers would circulate it, along with "Wanted" posters of the four officers, around the city. Reginald Schell held the highest post in the Philadelphia branch—Defense Captain. He was in charge, but to hear him tell the story (as he did to the author Dick Cluster), Philadelphia’s Black community residents—what Panthers and other Black activists simply referred to as "the people" back then—were the real Movement leaders. And, as Panthers would say, nothing would stop the people, especially not the pigs. The police raided the Panther office twice between June 1969 and September of 1970. It just helped the cause. Said Schell: "They understood that the more they attacked the Party, the more Black people came into the Party. And that the more Black people came into the Party, then around the world the more Third World people became conscious of the tremendous surge, the tremendous will that was developing in this Black ethnic group or race here in the U.S. They knew that they couldn’t eliminate us, because by the time they really started escalating the killings of Panthers across the country, the seeds of revolution were already sown in the people." The young Blacks who stood in the shadow of the Panther were self-sacrificing and energetic, remembered Schell.

At least one out-of-town Panther, a Marylander named Steve D. McCutchen, agreed. McCutchen (who, at the time, called himself "Chaka Masai" or "Lil’ Masai") kept a diary of his Panther activities. Laying low from The Man in Baltimore, McCutchen hung with Schell and the Philadelphia Panthers. McCutchen wrote the following in a June 1970 entry, published in "The Black Panther Party Reconsidered," a scholarly anthology: "Impressed with the Ministry of Information here. Wes Cook and his cadre supply sufficient and timely information to the community. I can learn from them." The Philly Panthers’ enemies equally appalled him: "[Philadelphia Police Commissioner Frank] Rizzo is a monster. His pigs are even more low-lifed than ours [in Baltimore]. He’s deadly and lets anyone and everyone know it. He’ll attack his own mother given the urge." And to Rizzo, the Panthers were a priority in the worst way. Abu-Jamal biographer Terry Bisson said the Philadelphia police "made the Panthers pay for every step they took. There were tickets for loitering, for littering, for jaywalking. There were midnight raids and searches." And then there were those impromptu intimidations police would make at Webb’s Bar, a Panther hangout. Recalled Schell: "We used to go into this bar over here afterwards, and I’d be sitting, talking to some people about some of the discussions in the [political education] classes. The FBI came in there and came up to me, and they had this police inspector with them, George Fencl, the head of the ‘civil disobedience squad.’ They asked, ‘Are you Reggie Schell?’ I turned around and said ‘No.’ So Fencl said, ‘Don’t play with me. That’s the m**********er right there.’ And they read the warrant and I was arrested." Police attempts to scare relatives of the Panther members were as unsuccessful as the other harassment methods. For example, Edith Cook, Wesley’s mother, knew her son was going to do what he wanted, so she ignored the warnings of the police and FBI. "Caution wasn’t part of my make-up at that age," Mumia Abu-Jamal told the activist/author Chinosole in a 1994 interview for "Schooling The Generations In The Politics Of Prison," an anthology she edited. "The point is that even then they were trying to disrupt human relationships, to inject fear and terror and to give the illusion that they were under every rock." But it wasn’t all deadly or serious. There were good times as well—jiving, shooting the s$%t, even falling in love and marriage. Many Panthers got married in Party ceremonies. McCutchen, in love with a woman named Connie, was one of them. "Can’t let this day go by," he wrote in a July 1970 diary entry. "Connie and I had a ceremony. A revolutionary ceremony. Reggie served as minister." With so much activity around him, Cook had decided to go with the revolutionary flow, embracing whatever it had to offer. He would spend the winter of 1969 in New York, and the spring of 1970 in Oakland, living and working with comrades in those cities. As a Panther, Cook had become a visible, committed revolutionary. Mostly invisible remained the federal authorities. The FBI tracked the Philadelphia teenager day and night—city to city, rally to rally, phone call to phone call. (NEXT: ‘Armed And Dangerous’: Tracked By The FBI) Copyright © 2004 by Todd Steven Burroughs. Used with permission of the author. |

Table of Contents

|

|

|

|

|

| photo of Mumia Abu Jamal | |

| photo of Steven Todd Burroughs

from Research Channel |

|