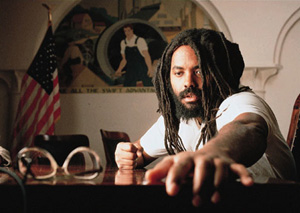

READY TO PARTY: MUMIA ABU-JAMAL AND THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY |

|

| by Todd Steven Burroughs, Ph.D. special to Prof. Kim's News Notes |

|

NOTE: In his new book, "We Want Freedom: A Life In The Black Panther Party" (South End Press), Mumia Abu-Jamal, a Pennsylvania Death Row inmate, remembers his Party days. In this excerpt, he discusses his transfer from his home base in Philadelphia to New York City, home of some of the most active Party branches and/or chapters on the East Coast. He was in New York for the winter of 1969-1970. "One could be transferred in the blink of an eye, for reasons that were beyond one’s ken," writes Abu-Jamal. "A Panther accepted this with equanimity or even looked forward to it with anticipation." Abu-Jamal references "The Panther 21," a group of New York City Panthers who were unsuccessfully framed by police for conspiracy, arson and attempted murder. –Todd Steven Burroughs A PHILLY PANTHER DISCOVERS N.Y.By Mumia Abu-Jamal I was excited when [I was] transferred to the BPP Ministry of Information in the Bronx, New York. The size and scale of New York’s five boroughs were stunning. It would take a vast metropolis like New York to make a city like Philadelphia seem small and somewhat parochial. The people of the Bronx were outgoing and warm in their response. Once, while we were racing from home on Kelly Street to the office on Boston Road near Prospect, we hailed a cab, and, as all five of us couldn’t fit in the back, the cabbie—a middle-aged guy who spoke with the Spanish-accented, broken English—invited one of us into the front seat, where he and his woman sat. He was a happy, gregarious man who exuded an infectious joi de vivre. He passed around hot, steaming English muffins to his riders and chatted amiably with us in a way that warmed us despite the biting New York winter all about us. I couldn’t help thinking that we wouldn’t have received such warm hospitality if we were in the city that claims to be reflective of brotherly love. Philadelphia never seemed smaller or meaner. New York’s branches were also unique in the racial composition of Party members, for it was the only site where Puerto Ricans served as Panthers. While they seemed to make up a higher percentage in Brooklyn, there were also some in our Bronx and Harlem branches. Some were former members of the Young Lords Party, who, because of their African heritage and their radicalism, felt more at home en Partido Pantero Negro. They gave the Party a deeper penetration in the communities of color in New York and served with both pride and distinction. New York seemed like an ethnic and cultural stew that was far more varied and textured than its Oakland-based progenitor. In New York, for example, a significant portion of the Panthers were Sunni Muslims, as many of them either knew personally, or profoundly respected the Sunni-convert, Al Hajji Malik El-Shabazz (Malcolm X). Indeed, Dr. Curtis Powell (one of the famed "Panther 21") met and talked with Malcolm in Paris after his pilgrimage to Mecca. Fellow "Panther 21" veteran Richard Harris heard Malcolm preach as a Black Muslim minister at the Newark [N.J.] Temple. As a consequence, the National Office saw the New York branch as somewhat skewed, as perhaps tacking toward the dreaded heresy of "cultural nationalism." In New York, Panthers boasted African or Islamic-oriented names, had Hispanic names or accents, wore African or traditional garb, and were riotously independent. The secular, uniformed center in Northern California always looked at New York as a wildly undisciplined younger brother (with a larger membership). If Philadelphia was busy, then New York was a frenzy. Everywhere one turned there was something new to learn about this vast new tableau. In Philadelphia, Broad Street was the main artery, dissecting the city into North and South Philadelphia. If you knew Broad Street, you knew Philadelphia. What in the name of Heaven did one do in New York, where five huge cities (they called them "boroughs," but they looked like cities to me) converged into an amorphous, octopus-like mass of confusion? Manhattan? The Bronx? Harlem? Queens? Staten Island? IRT? IND? New York was a vast puzzle that a young Philadelphia Panther tried to solve daily. Native New Yorkers rarely helped, for they assumed that anybody with half a brain would know, almost instinctively, what the IND or IRT lines meant in the subways. I had to learn how to ask questions and how to pick up keys for what train went where, and when. It was dizzying and challenging. More than once I dozed during a subway ride, only to awaken on a darkened car, out in some huge, dark subway yard, and had to find my way back. Many times I spent hours walking from place to place, selling papers or traveling from our office to the apartment. I was more confident in my walking than engaging the alphabet soup of the subway and El system. Copyright © 2004 by Mumia Abu-Jamal. Excerpted from "We Want Freedom: A Life In The Black Panther Party," published by South End Press. Reprinted with permission from South End Press. |

Table of Contents

|

|

|

|

|

| photo of Mumia Abu Jamal | |

| photo of Todd

Steven Burroughs

from Research Channel |

|