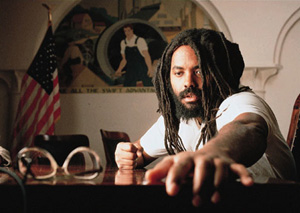

READY TO PARTY: MUMIA ABU-JAMAL AND THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY |

|

| by Todd Steven Burroughs, Ph.D. special to Prof. Kim's News Notes |

|

Part One:"DO SOMETHING, NIGGER!"By Todd Steven Burroughs Wes Cook was (and is) an explorer and an adventurer. He thrives on intellectual challenge and feeds on the adrenalin rush of the quest. In the 1970s, being a radio journalist, he fulfilled these needs as Mumia Abu-Jamal; but that identity was far ahead of Wesley Cook as he turned 15. He was neither a radio journalist nor an international cause celebre nor yet a man, although friends and family said he often carried himself like one. Cook was a teenager in search of his manhood and identity during a time when his people openly sought their destiny. "I remember—and of course we’re talking about decades ago now—but I remember it was probably one of the most exciting and liberational times of my life," Mumia Abu-Jamal recalled to an interviewer in the appendix of "Death Blossoms," his second book. "Of course, for most people, their teen years are a time of freedom. Mine were a time of ultra, super freedom. It was a tremendous learning experience." Enter the Black Panther Party. It was 1969 when Cook helped form Philadelphia’s BPP branch. It was a time to be young, angry and Black. Like many Black teens of the time, Cook wanted outlets—for camaraderie, for expression, for resistance, for nia (meaning "purpose" in Kiswahili). There were many choices for young Blacks who were also looking for those things. They included the Nation of Islam, the NAACP, and various Black cultural nationalist organizations in colleges and/or on the streets. For Cook, the Black Panther Party’s Philadelphia branch satisfied those four needs. "As a fourteen-year-old, I joined the Black Panther Party and became part of a revolutionary formation dedicated to defending the Black community," Abu-Jamal recalled years later in an anthology on Black men edited by Essence magazine. "I felt like a man. I joined the Party about a year after another man, Bobby Hutton, was murdered by Oakland cops, and[,] like Bobby, I was fully prepared to give my life in defense of the Party and our people’s righteous struggle for freedom and self-determination. Man, then, meant militant defense, service, and sacrifice for one’s people, one’s community and one’s Party." Bonding happened quickly between Cook and his fellow Panthers, most of whom were at least five years older than him. Cook’s "father hunger," as he would label it later, was particularly satiated by his relationship with Reginald Schell, the branch’s captain. The recent death of "Mr. Bill," Cook’s father, had, like the Movement, moved adulthood a little closer. Acting more like a big brother at home to try to fill the absence of "Mr. Bill," Cook would happily embrace the role of Schell’s little brother while they worked for the people. Their friendship and working relationship would be birthed by, and would survive, the Party. (Like Cook, Schell—whose official title in the Philly BPP was Defense Captain, the highest rank in a branch—was a working-class Black man who wanted to be more involved in the Movement. He left a foreman job at a sheet metal company in order to be part of the BPP’s Philadelphia branch. He recalled in Philadelphia Weekly, an alternative newspaper, how his wife initially thought he lost his mind when he told her his plans to be part of a Panther chapter. "I told her, ‘I can’t take this s**t no more.’ Blacks getting killed in the South because they were trying to vote, dogs getting sicced on them. My mind couldn’t just compute that.") In "Death Blossoms," Abu-Jamal, always aware of his status as a "political prisoner," publicly remembered his relationship with his Panther brethren the way a revolutionary would: "Without a father, I sought and found father figures like Black Panther Captain Reggie Schell, Party Defense Minister Huey P. Newton, and indeed, the Party itself, which, in a period of utter void, taught me, fed me, and made me part of a vast and militant family of revolutionaries. Many good men and women became my teachers, my mentors, and my examples of a revolutionary ideal—Zayid Malik Shakur, murdered by police when Assata [Shakur] was wounded and taken, and Geronimo ji jaga (a.k.a. Pratt) who commanded the Party’s L.A. chapter with distinction and defended it from deadly state attacks until his imprisonment as a victim of frame-up and judicial repression—Geronimo, torn from his family and children and separated from them for a quarter of a century." THE PARTY NOT only gave Wes Mumia Cook (as he now called himself) a second family, but also a single outlet for his creativity, his intellect and his sense of rebellion: revolutionary journalism, in the form of his post as the branch’s Lieutenant of Information. Being a propagandist suited him; Schell noticed Cook could put words together well, both verbally and in print for The Black Panther national newspaper. His Black Panther bylines varied with his nicknames: Wes Mumia, West Mumia, Mumia X and Bro. Mumia. His articles read like those of a recent convert ("Throughout our history, some niggers have refused to bow down and be beaten into the dust"), reflecting the defiant anger—and, some Panthers and others would say years later, the political immaturity—of the time. His articles, like most in the Party newspaper, would end with some sort of proletarian call to action: "Do Something, Nigger, [Even] If You Only Spit!" Cook had found a career that he would use to define himself as his life took many turns. School just couldn’t compete with the intellectual immersion that journalism required and the excitement it and the other Party work generated. It wouldn’t be the last time Cook would bounce back and forth between formal education and its more gregarious, dynamic, lower-class, creative, free-spirited and attention-seeking cousin. With his path set, Cook became a fulltime revolutionary. He dropped out of Benjamin Franklin High School and took up residence in the branch’s headquarters. Cook’s family trusted him to find his own way, so they put up no resistance. As spring became summer and summer became fall, Cook’s days and nights in 1969 quickly became centered around three things: Party work, his family, and a young woman named Francine Hart. She was attracted to the tall, Afro-ed Panther with the deep voice, even though he was younger than her. Cook gave her a new name fitting a revolutionary—Habibah. Soon he and Biba, as she was nicknamed, seemed attached to the hip, becoming regulars at rallies, streetcorners (selling the newspaper) and Robbens bookstore downtown. From a Death Row cell, Abu-Jamal has publicly ruminated on the tenuous state of young Black manhood. Every young African-American male still has the choice he faced decades ago: to be consumed by anger or to constructively channel it; to embrace self-pity or seek higher ground. "One can emerge with the poison of aloneness, or the shared sense of commonality," he postulated in the Essence anthology. The teenage Cook chose to be pro-active, to emerge with the latter. He was also fortunate to have a Movement that easily absorbed his energy. Cook had begun to meet his teenage desires—to "do something" to nourish himself. He embraced his adventure into young manhood. As a result, Cook gained a new family that was helping to fuel a revolutionary spirit of Black unity. He enjoyed both while they lasted. (NEXT: The Party In Philadelphia) Copyright © 2004 by Todd Steven Burroughs. Used with permission of the author. |

Table of Contents

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| photo of Mumia Abu Jamal | |

| photo of Todd Steven Burroughs

from Research Channel |

|