TOLERANCE

A large cloud of smoke drifted my way, and my friends and I ducked and tried to move out of the way. We were unable to escape its foul smell as it wafted over and around us, leaving particles of residue in our clothes and lungs. I couldn’t help but think about all the forest fires that raged only two months earlier during the summer I spent in Colorado.

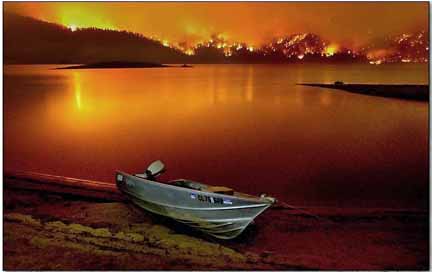

I was in Denver when the Heyman fire deposited smoke and ash over much of the city, causing the hospitals to be overrun with emergencies from people with respiratory problems. I fled Denver and headed up into the high country, but first I had to use a broom to sweep ash off my truck windshield before I could drive. A month later, at my house in the mountains, I was put on evacuation standby for two days as planes circled my house dropping fire retardant and helicopters dropped water on a fire that was only three miles away. The visibility was down to less than a quarter of a mile from the smoke and ash, and I had to take refuge inside with my house closed up tight.

Now, however, there wasn’t any forest fire. It was a nice warm fall day, and some friends and I were outdoors at a jazz festival where recent rains had provided temporary relief to the drought that had plagued the East coast and much of the country. This latest cloud of smoke was from a cigar that a guy was puffing on about 10 feet away, and from the cigarette smoke of his two friends. I watched as the breeze shifted and started blowing their smoke in a different direction, causing other people to dodge and look annoyed. I was reminded of a photo I saw during the summer of fire fighters who had been fighting one of the many forest fires. They were taking a rest break from their work and looking very exhausted. Their clothes were covered with ash and soot, and their respirators hung from their necks. And they were smoking cigarettes.

I don’t suppose people who smoke see the irony in this, and I wondered if fire fighters who smoke have some extra tolerance or immunity to wood smoke that enables them to work more effectively in such environments. I realized that smoking is not a habit, it’s an addiction, just like cocaine or heroin, and that it has no benefits except to those who sell the products. And for a moment or two I felt sympathy for the people who were smoking. Then the wind shifted my way again and I wanted to beat the crap out of them.

Out of this experience came a new understanding of the word “tolerance.” According to Webster, tolerance is, “a fair and objective attitude toward opinions and practices that differ from one’s own.” I now have an appreciation for how easy it is to be tolerant when the smoke is blowing the other direction.

In a larger sense, it is easy to be tolerant of things to which one is not directly exposed. We pay to see violence at the movies, but call the police when it happens in our own back yard. We laugh at stupidity on TV but get annoyed if we encounter it in person. And we tolerate politics as long as we get what we want. When I see people smoking, if I think to myself, ‘You poor bastards are slowly killing yourselves and you need help,’ that’s sympathy. If I say to myself, ‘You poor bastards are slowly killing yourselves, but that is your right,’ then that is tolerance. When I smell people smoking and I think to myself, ‘You bastards better stop smoking or I’ll kill you,’ that’s intolerance.

Tolerance is thus a matter of involvement. The more removed from reality we are, the easier it is for us to be tolerant. Or as they say in the West, “Always drink upstream from the herd.”