"LET’S GO FOR IT!"

It started out innocently enough, as most days do. I’m not quite able to pin point where things got out of hand, but then it really doesn’t matter. Bad situations often develop out of a series of contributing events, each one rather insignificant in and of itself. In the aftermath there is often someone or some group ultimately responsible for overall results who attempts to "what-if" a situation to death in an effort to justify their position of responsibility and to affix blame. Fortunately for me, no one person was ultimately responsible -- except perhaps me, and I certainly wasn’t going to conduct my own inquisition.

It was Thursday, and like all Thursdays at our Colorado Guest Ranch, the guests for the week were primping and putting on their newly acquired cowboy and cowgirl clothing for the photo session that was to be conducted before and during the morning breakfast ride. In each of the 12 guest cabins, new boots, new hats, fancy shirts, bandannas and new jeans, and in some cases new chaps and spurs were being modeled in front of mirrors and admired by other family members. I guess it is one reason guests are called "dudes." No self-respecting cowboy would be caught dead in an all-new outfit, even if he could afford it. And certainly he would not wear it to ride a horse. Most new outfits, rare that they are, are saved for the Saturday night rodeo. But then, most self-respecting cowboys wouldn’t work at a dude ranch, so who am I to talk?

For the Thursday photo session, the normal 8 AM breakfast in the lodge is replaced by an outdoor breakfast cookout on Saddle Mountain, about two miles from the ranch. Guests meet at the barn around 9 AM for family and individually posed pictures. Smiling dudes in their finest gear, some holding lariats, pose by old wagon wheels, sun-bleached cow skulls, elk antlers, hay bales and other western props. Never mind the fact that the dudes look about as authentically western as a dime store Santa Claus. The photos will adorn tables, walls and book shelves for decades as testimonials to the western adventure they had one week way back when.

After all the pre-ride photos are taken, the guests mount up and ride out in groups for other posed photos on their horses. Each wrangler takes his or her group on the 20 minute ride up to Saddle mountain where the photographer takes photos as the guests ride by. Snow capped mountains provide a panoramic backdrop, and the new outfits become less dominate but still obvious. By dinner time, the photographer will have returned to the ranch to provide a slide show of all the days shots -- usually about 100 or so. Then everyone lines up to place their orders for enlargements, Christmas cards, tee shirts with photos on them, cutout photos, etc. The most I ever saw a family order was $700 worth. Vanity becomes more expensive for people who have large families.

This day I was assigned the fast group. What that means is that all of the riders in my group have lied about how well they can ride in order to be able to experience galloping on a horse. Perhaps this was the first in the series of contributing events - the fact that some of my group had lied about their riding prowess. I take no responsibility for this first contributing event, because I am not the person who assigns the riders to groups. Steve, one of the owners, must take the blame for that one.

The second contributing event was an act of God -- or perhaps the devil. My horse Black Jack was missing a shoe, so I had to find a substitute, and there weren’t many. We had a full guest list this week and almost all of the usable horses were assigned. We had our usual "down list" of horses needing shoes, sick horses, or in Butter’s case, just not safe for riding. I got Butter.

Butter is the color of butter, but the similarity ends there except for the fact that too much butter is bad for your health. Butter had not been ridden for quite a while because he was not safe to put guests on, and the wranglers all had their "wrangler horses" to ride. Earlier in the season, a "highly skilled" rider (a guest’s self description) was given Butter to ride and, after 15 minutes in the arena with Butter, was begging for another horse. Now it was my turn.

I approached Butter with great confidence and brought him out to groom. Butter is very nice and friendly. It is just that when someone gets on Butter he is very hard to handle and likes to rear up and run away with you -- assuming you are still on him. Because of this, he has a double-cinched saddle with breast collar, a tie-down to keep him from raising his head too high, and a rather severe curb bit for additional control. I always ride bareback, so I decided to dispense with all of this.

Riding bareback is a habit I got into a few years earlier, and I don’t use a bit or bridle. In fact, on my horse, I use no tack at all except for a neck ring made out of rope. Part of this comes from my desire to get back to my Indian roots. The other part is just stupidity. There are a number of good reasons why most horse people, and all cowboys and wranglers, don’t ride bare back. You can’t carry much gear, your butt gets really dirty, the horse sweat soaks through your underwear making you feel like you’ve wet your pants, and you tend to fall off every time something scares your horse. In the two years I have been riding bare back, I have made several trips to the hospital, torn ligaments in my hip, knee and shoulder, and had surgery once. I’m beginning to think Alex Haley had a much better way of getting in touch with his roots.

Being well aware of all of this, I decided I would ride Butter bareback and use a bosal. A bosal is a braided rawhide loop which goes around the horse’s head a few inches up from his nose and is attached to a head stall to keep it in place. It provides some control without using a bit. Indians used them. My fellow wranglers were in awe -- which in cowboy country means they called me a dumb shit but were secretly envious. The guests were very impressed, and I was eating it up.

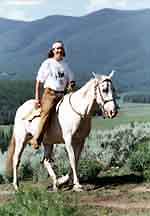

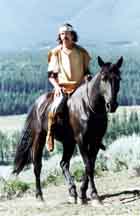

To add to the effect, and to help me get in touch with my roots, every Thursday I dressed as an Indian. On this day I was wearing my deer skin moccasins which laced up to just below my knees and my sleeveless deer skin shirt which consisted of two skins sewn together with a hole for my head to go through. I did forego my deer skin loin cloth and wore light tan jeans with fringed deer skin chaps. And of course I had my deer skin headband with two eagle feathers hanging down in back. All in all, I looked pretty authentic except for my mustache.

The ride up to Saddle Mountain was uneventful except that I did get a good picture of me riding Butter and looking very native American. I would have looked great in an ad for Colorado spring water or in a tourism brochure. My group was chomping-at-the-bit, to use a trite expression, and could hardly wait until after breakfast for their 3-hour ride to new and exciting places and the chance to ride a galloping horse.

Barry, a Jewish anesthesiologist from Chicago, was on vacation with his girl friend, an x-ray technician. Barry was one of the more vocal members of my fast group and, by the time breakfast was over, he had convinced several other guests to join the "fast riders" -- a name he had coined to add status to the upcoming event. The growing size of my group was another event in the series of contributing events. There were now eight members. We generally try to keep groups to no more than six or seven guests per wrangler guide. The more adventurous or fast the group plans to be, the smaller the group should be. The idea is that the wrangler must keep an eye on all of his riders for any problems. Things like loose cinches, broken tack, thrown shoes, injured or lame horses, and a host of other possible problems that might arise. Watching for such things is harder to do the faster you go. We were now a large, fast group.

It was a little before 11 AM when I led my "fast riders" out of the breakfast area. I decided to break them in by doing some trail blazing, so I led them down a steep winding hill partially covered with sage brush, pine and aspen trees. The comments I heard behind me from my group as we descended the hill should have been another clue that these folks weren’t really ready for prime time. "Oh my God this is steep." "My horse isn’t going to make it." "Snowy River here I come." "If I live through this, I will never wear white underwear again."

At the bottom of the hill we forded a stream where some horses jumped and others balked. We came close to losing a few riders in the water, which was added evidence of the folly we were undertaking. But everyone was having a great time, in spite of their few moments of expressed, and sometimes silent, terror. I am convinced, after observing and leading guests on mountain trail rides for the last seven summers, that people take risks and attempt daring feats in the presence of new friends and new environments that they would never consider doing alone or in familiar surroundings. The "lets go for it" attitude is probably the one group phenomenon that gets us all in trouble at one time or another. Like the time four of us wranglers decided to go for a midnight ride and ended up loping along a winding mountain trail that was so dark you couldn’t see the ground or your own horse’s head. The horses can see where we can’t, and they knew the trail, so we let them go. It was blind faith backed up by group stupidity, and precipitated by someone saying: "Lets go for it."

We take all of the fast rides up on the flats where long stretches of sage brush and cattle paths run along the top of a bluff for about two miles. It allows for running because it is level, and I know where all the gopher holes are located. One running horse stepping into a gopher hole, and you end up with a seriously injured horse and rider. We have to shoot the horse, but the rider gets to go to the hospital.

About 20 minutes into each ride, the wrangler dismounts and checks each of the guest horses to make sure the cinches are tight. Usually some have loosened by this time -- especially after going down a steep hill. I dismounted to check the horses before taking on the flats. The only problem with my doing this is that riding bareback means no stirrups, so it requires some skill in remounting. Butter was not accustomed to a rider running toward his side and jumping up on his back. Unlike my horse, he kept moving away when I would take a few quick steps toward him. When I tried compensating for that by an extra quick step and a stronger than usual leap, I went too far over his back and landed on the ground on the other side in a rather uncompromising position. It was very entertaining for the guests, but rather humbling for the experienced wrangler dressed as an Indian.

We began loping, or cantering as the English riders like to call it. Everyone was loving it. I kept an eye on the folks and noted a few death grips on saddle horns, a sure sign of an inexperienced rider. Seasoned riders never hold the saddle horn unless they lose their balance. Inexperienced riders always grip the saddle horns because they either have no balance or are very afraid. Riding bareback, I have nothing to grip that would help, so I either keep my balance or fall off. Butter was doing great and I was becoming fond of him and very impressed at how well he was behaving.

We spent an hour or so exploring the lower valley area north of the flats and then returned to the flats where I prepared everyone for the really fast part of the ride. The excitement was building and someone said "Lets go for it!"

I should have known better, since this was a two mile straight stretch heading back toward the barn. The horses always like to go faster when they are coming home from work. I gave the signal and kicked Butter into high gear. It turned out that high gear for Butter was far in excess of what my horse could do. My fast group quickly got stretched out well behind me and it was a horse race between me and Barry’s girl friend who was an excellent rider. She and I ran the entire two miles at break neck speed and Butter still didn’t want to stop when we approached the end. The end was marked by a steep ravine that would have been certain disaster for both of us. I managed to stop Butter and look back at my group members who were strung out over the previous mile.

My first clues that something was wrong were the two horses that came running up with no riders on them. My second concern was that several riders had turned around and were riding in the direction from which we can come. I kicked Butter into high gear once again and we raced back toward a situation that I could only imagine to be horrible.

The first of my group I encountered were the two riders who had lost their horses. Fortunately they were bruised and agitated, but not seriously hurt. At least not until the next day when they couldn’t move. Both of their horses had been spooked by a dead cow that we had run past. They said they lost control, which they probably never had in the first place, and fell off while their horses were trying to stop. If you are going to fall off a horse, it will probably be when your horse is stopping rather than while it is running. We call it the forward dismount. Their gait is rough and bouncy as they put on the breaks -- especially when you are not expecting it.

With these folks in recovery mode, Butter and I continued back to where my remaining guests were congregating. When I got there, Barry was sitting on his horse with blood all over his face, shirt, pants, boots, and on his horse. It looked like he had been attacked by a band of Indians wielding tomahawks. He could not see because of the blood in his eyes, and his glasses, or what was left of them, were mangled and lying on the ground. He was in shock. It was the worst I have ever seen anyone look on a horse, and I couldn’t understand how or why he was still mounted.

When it all got sorted out, Barry admitted that he was really uncomfortable galloping (translated: He was scared out of his wits). When he tried to stop his horse, who was trying to keep up with all the other running horses, his horse got agitated and started throwing its head back. The slowing had propelled Barry forward and his face collided with the horse’s head, smashing Barry’s glasses into his face and putting a fairly significant gash above his eye. The good news was that we had a doctor in our group. The bad news was that it was Barry.

We eventually got Barry’s bleeding stopped, rounded up the runaway horses and all of us rode humbly back to the ranch at a slow walk. Pam (another wrangler) and I drove Barry and his girlfriend to the hospital -- a place I was quite familiar with. While Barry was getting stitched up at the hospital, Pam went across the street and bought a horse trailer. I went down the street and bought a cheeseburger and milkshake at the Dairy King. (We wranglers try not to let adversity interfere with our day-to-day life.)

The story ends on a rather ironic note. Barry has since purchased 30 acres of land about two miles south of where he bashed heads with his horse. He and his girlfriend are planning to build a home there. The two folks who fell off their horse have made reservations to return to the ranch next year, and I fell in love with Butter (so to speak). I don’t know if there is a moral to this story. Perhaps out of adversity, good things often arise, and good memories often replace bad ones. I am more careful now about whom I take on fast rides, but I always know that there are risks, and perhaps taking them is what makes life more exciting and worthwhile. Why else would a 55 year old business professor, dressed as an Indian, be galloping bareback on a strange horse across Colorado high country leading a Jewish doctor and seven other novice city folks on an adventure they shall never forget?

• • •