|

Since the dawn of

human history, when our ancestors first migrated into cities and

established distinctive societies, certain predicaments have inevitably

plagued all civilizations. Though war, disease, and famine have all played

their part in modifying the ebb and flow of history, some of the most

significant revolutions and movements in history have occurred because the

poor, downtrodden masses are forced to endure harsh, unreasonable, and

ultimately cruel measures at the hands of the corrupt establishment. In

the twentieth century, as mass media came to fruition, music became an

increasingly popular mode of influencing both ‘the Man’ and his victims.

But even though social movements may be separated by geography, time, and

style of music, their penultimate messages resound across these boundaries

to enact change and reform.

In the early

twentieth century, labor disputes were coming to a head. Aggravated by

poor conditions, low wages, and oppressive management, the American

proletariat was turning toward radical groups like the Industrial Workers

of the World. The IWW, or the Wobblies, as they were commonly called,

urged a massive class war that would ultimately end with the complete

overthrow of the petty bourgeois. One of the chief mediums for spreading

the IWW’s message of content was song. Because the heyday of the Wobblies’

struggle took place before the proliferation of radio, they relied on

contracted singer/songwriters to write fiery ballads of revolution and

would then print the lyrics and music and distribute them for a small fee,

simultaneously spreading the word and raising precious funds. In the early

twentieth century, labor disputes were coming to a head. Aggravated by

poor conditions, low wages, and oppressive management, the American

proletariat was turning toward radical groups like the Industrial Workers

of the World. The IWW, or the Wobblies, as they were commonly called,

urged a massive class war that would ultimately end with the complete

overthrow of the petty bourgeois. One of the chief mediums for spreading

the IWW’s message of content was song. Because the heyday of the Wobblies’

struggle took place before the proliferation of radio, they relied on

contracted singer/songwriters to write fiery ballads of revolution and

would then print the lyrics and music and distribute them for a small fee,

simultaneously spreading the word and raising precious funds.

Among the most

famous of these hired lyricists was Joe Hill, a Swedish immigrant whose

ballads emphasized the labor struggle with their caustic edge. Hill

achieved national notoriety when he was executed for a murder in Utah,

having been quickly tried and killed on extremely circumstantial evidence.

The IWW promoted him as a martyr of the cause and sales of his songs

increased substantially. Hill’s most famous song, “The Preacher and the

Slave” is a parody of “In the Sweet Bye and Bye,” a popular hymn that

promises eternal rewards for earthly piety and support of the church.

Hill’s version contained many sardonic puns, even referring once to the

Salvation Army as “the starvation army.” At the end of “The Preacher and

the Slave,” Hill, in line with the IWW’s goals, encourages a radical

revolution, urging “the workingfolk of all countries” to unite against

their oppressors and fight “side by side” for the “world and its wealth.”

Such a radical,

combative message was hardly uncommon. Indeed the IWW’s constitution

states that “between these two classes a struggle must go on until the

workers of the world organize…take possession…and live in harmony with the

world.” This militant message would ultimately lead the IWW into trouble

with the government and an eventually decline, but the struggle for

economic and social equality has continued in its absence.

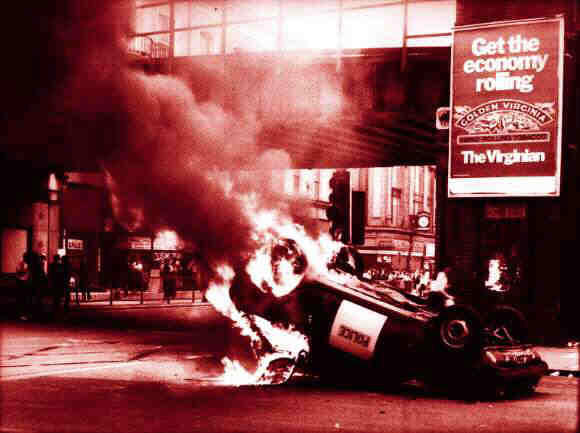

In the late 1970s, a

new musical revolution was occurring in England. Fed up with the

commercialization of rock and roll, social outcasts collectively known as

the punks began to experiment with new types of music, creating a sound

that was wholly unique and anti-establishment. Punk has its roots in the

sound of bands like the Kinks and the Who, with explosive anthems like “My

Generation,” which emphasized youth culture and passion with lyrics like

“I hope I die before I get old.” By the time true punk materialized in the

Seventies, bands like the Ramones and the Sex Pistols were leading the

revolution. However, it was the Clash that would come to truly epitomize

the punk ideal and attitude, achieving their iconic status with their 1979

album London Calling. The album, with its legendary cover of

bassist Paul Simonon smashing his bass guitar, successfully fused the

Clash’s politically charged punk with a variety of world beats. This

blending of punk and reggae produced one of the most well known tracks off

of the double album, “The Guns of Brixton.”

“The Guns of

Brixton” refers to building social unrest in London in the late seventies

and early eighties. Brixton is a neighborhood in southern London which is

overwhelmingly poor, overcrowded, and rife with both crime and an inherent

distrust of law enforcement. In response to the abundance of crime, police

forces began to enforce an obscure segment of an 1824 law to accost and

arrest individuals based solely on the suspicion to commit a crime. These

codes, commonly referred to as the “sus laws” resulted in a massive

violation of civil liberties and due process. As a result of the economic

conditions and police harassment, Brixton became a volatile powerkeg

waiting to explode.

In the song,

writer/bassist Paul Simonon takes a similar approach to Joe Hill, urging

revolt against the sus laws. However, Simonon’s lyrics lack Hill’s cynical

humor. Instead, the Clash song is full of a fiery rage. Simonon demands

listeners make a choice:

“When they kick in

your front door

How you gonna come

With your hands on

your head

Or on the trigger of

your gun?”

Simonon presents a

bleak decision – either comply with the unjust sus laws or die in a hail

of bullets, “shot down on the pavement.”

He shares this

retaliatory sentiment with Hill. Both writers are fermenting rebellion

among the lower classes, the downtrodden, oppressed proletariat. Hill and

Simonon both specify a target; in “The Preacher and the Slave,” hill

targets the bourgeois grafters and the “starvation army” while Simonon

attacks “the law,” the policemen enforcing the unfair statutes. Each song

is harshly critical of the establishment for their complicity in the

problem at hand.

However, for all of

their similarities, “The Guns of Brixton” and “The Preacher and the Slave”

are two very different songs. The most obvious difference is the style of

music. “The Preacher and the Slave” is a traditional folk hymn. It is

designed to be sung a capella or with only an acoustic guitar

accompanying. “The Guns of Brixton” is a completely different affair. It

is a punk song, a genre which endorses anti-establishment beliefs and

attacks the traditional. The song possesses a Jamaican influenced reggae

beat with a prominent bass-line and reggae-style upstrokes on the guitar.

In addition to

differences in style, the two songs, though they possess similar prognosis

and motivation, differed in results. Though the IWW was fairly militant

and known for inciting riots, “The Preacher and the Slave” held a more

broad target and objective, one that would never see fruition in the

United States. “The Guns of Brixton” however continued to stir unrest and

discontent in Brixton, which erupted into the most vicious riots

Britain

had ever seen and sparked further rioting on a national scale. These riots

ultimately resulted in the repeal of the hated sus laws.

Though Joe Hill and

the Clash wrote and performed very different types of music in very

different eras, the two share common, universal elements. Both songs deal

with a universal human condition and suggest similar ways of fixing the

situation. For all their differences in style and result, “The Guns of

Brixton” is a spiritual successor of sorts to Joe Hill’s classic protest

music.

|