Since its inception more than a quarter century ago, punk rock has been

an enormous and integral part of popular music. Many of punk’s

progenitors considered themselves social outcasts, excluded from

mainstream society. Despite their somewhat anti-social beliefs, punk

musicians soon found legions of followers, who emulated the early punks’

style of dress, speech, and ideology, thus spawning a unique, separate

subculture complete with its own collective identity. Two factors

contributed to the creation of a collective punk identity. The first was

punk music itself. In lyrics that were often angry and spiteful, the

disillusioned children of the Vietnam era found sentiments to which they

could relate and slogans with which they could sing along. The second

key factor in the creation of punk’s collective identity stemmed from

simple imitation of the musicians themselves. Legions of fans came to

follow in the footsteps of punk musicians, copying their styles of

dress, their hairstyles, and their views.

The punks were the children of the Vietnam era. A decade of war,

credibility gaps, and White House scandal left the punks with a strong

sense of animosity and distrust for the government. Coupled with a

declining economy, the social situation in America was ripe for the

birth of punk. At the same time the necessary prerequisites for the

British punk scene were developing as well. England, like America, was

in a fierce economic slump, following World War II and the subsequent

collapse of the British Empire. Without her imperial holdings, the

United Kingdom’s economy was stuck in a sharp rut, and the immigration

influx that followed in the wake of decolonization only furthered Great

Britain’s economic woes. Under such harsh conditions, both the American

and British youth held a bleak outlook on the future. Punk rose amidst

this social and economic depression, with three acts rising to

prominence in the punk scene. The Ramones, the Sex Pistols, and the

Clash are arguably the three most influential punk bands, both in terms

of influencing each other and influencing the creation of a collective

punk identity.

The Ramones, the only American act out of the three, were the pioneers.

The first band to truly embody all of the punk characteristics, the

Ramones wrote bizarre, random songs. Their musical style was angry and

blisteringly fast, and their lyrics often contained references to drugs

or similarly offensive material. “No I Wanna Sniff Some Glue” and “I

Wanna Be Sedated” both reference drug use, which was becoming

increasingly common among the youth of America. As such, listeners could

relate to the Ramones’ lyrics, sympathizing with them. In addition to

relating to drug use, punks were awed by the Ramones’ flagrant disregard

for societal norms. Many of their songs contained both blatant and

subtle references to offensive groups like the Nazi Party and the KKK.

“The KKK Took My Baby Away” is among the most blatant of these offensive

songs, but the title of “Blitzkrieg Bop” refers to the chief Nazi

strategy early in the Second World War. The Ramones disciples engaged in

similar behavior, like the Ramones, they did it not out of any real

hatred or sympathy with hate groups, but instead a desire to shock and

offend, a desire to be noticed by a society that ignored them.

The Clash and the Sex Pistols also sang songs that people could relate

to. The Sex Pistols’ lyrics were laced with scorn and angry at the

government. They sarcastically sang “God Save The Queen,” which

sarcastically and scathingly criticizes the British government,

satirizing the original “God Save The Queen” which is a patriotic

anthem. Like the Ramones, the Sex Pistols also worked to be offensive;

in “Anarchy in the U.K.” Johnny Rotten screams that he is “an

anti-Christ” – a particularly offensive statement to the largely

Christian English.

On the other hand, the Clash, though they emerged from the same scene as

the Sex Pistols, espoused lyrics that were, at most, only mildly

offensive. Instead, the Clash were separated not only by their far

superior musicianship (for they were one of the only punk bands to be

made up of talented musicians), but also by the left-wing politics they

advocated with their lyrics. The Clash sang about all of the economic

and social problems facing not only Britain, but often the entire world.

In “White Riot,” the Clash’s first single, Strummer shouts, “black man

got a lotta problems, but they don’t mind throwin’ a brick…too chicken

to try it.” Strummer continued to urge revolt against the government’s

poor treatment of the working class, both black and white. In “Guns of

Brixton” he attempts to incite armed resistance to the brutality

demonstrated by police. In “Remote Control” the Clash question

government authority, asking “Who needs remote control from Civic Hall?”

As the economic slump in Britain continued to deepen, and racial

tensions continued to rise, the Clash’s lyrics were poignant reminders

to the British people of the flaws in their society. Listeners flocked

to the Clash’s punk banner, for the Clash promoted ideas with which they

could agree.

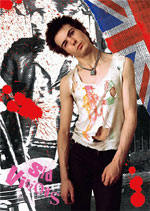

In addition to commiserating with their audiences through their lyrics,

punks helped form a punk subculture purely by example. Due, to some

extent, to the brilliant managing of entrepreneur Malcolm McClaren, a

clothing store owner, the punks, particularly the Sex Pistols, set

fashion trends, and created a fad. The Ramones dressed like

nineteen-fifties tough guys, with leather jackets, white shirts, and

tight jeans. The Sex Pistols followed suit, with the same tough,

hard-edge look. The punks ripped their clothes and wore spiked and

colored hairdos. They wore offensive symbols on their clothing, like

swastikas, or other white-power symbols. The styles the punks adopted

were designed to completely and totally emulate their musician-idols.

Everything about the punks’ style stemmed from a desire to offend and to

be noticed. The punks were members of a generation that had been all but

forgotten by their governments, who were too busy trying to rectify old

mistakes and attempting to prevent war aboard that they failed to notice

the plight of their own citizens.

In addition to commiserating with their audiences through their lyrics,

punks helped form a punk subculture purely by example. Due, to some

extent, to the brilliant managing of entrepreneur Malcolm McClaren, a

clothing store owner, the punks, particularly the Sex Pistols, set

fashion trends, and created a fad. The Ramones dressed like

nineteen-fifties tough guys, with leather jackets, white shirts, and

tight jeans. The Sex Pistols followed suit, with the same tough,

hard-edge look. The punks ripped their clothes and wore spiked and

colored hairdos. They wore offensive symbols on their clothing, like

swastikas, or other white-power symbols. The styles the punks adopted

were designed to completely and totally emulate their musician-idols.

Everything about the punks’ style stemmed from a desire to offend and to

be noticed. The punks were members of a generation that had been all but

forgotten by their governments, who were too busy trying to rectify old

mistakes and attempting to prevent war aboard that they failed to notice

the plight of their own citizens.

The ease with which the punks adopted their heroes’ styles was due in

part to a sense of solidarity with the punk bands, and in part to

extremely savvy promotion by managers and record company executives,

most notably Malcolm McClaren. The owner of a store called SEX, which

specialized in a variety of leather products, including myriad fetish

wear, McClaren formed the Sex Pistols to promote his store. The members

were hand-picked to be walking billboards for the store, and their very

names were manipulated to fit a hardcore punk image: Simon Ritchie

became “Sid Vicious” and John Lydon was transformed into “Johnny

Rotten.” With a variety of well-staged publicity stunts, the Sex Pistols

became famous, prompting their fans to adopt their style of dress. Of

course, all of the punk-wear could be conveniently purchased from

McClaren’s SEX store. Thus, under McClaren’s management, punk became

trendy, spawning hordes of fans who were just as upset with the

government as the punk bands were, and willing to spend money to emulate

their idols.

Punk’s collective identity is, in some ways fairly tenuous. Members may

have widely varying political beliefs, with some believing in anarchy

and social nihilism, while other punks espouse the Clash’s activist

philosophy. The styles of dress among punks even vary significantly, as

a simple comparison between the Ramones and the Sex Pistols reveals.

However, the punks are united by a single pervasive theme: distrust and

scorn for the governments that continually neglected their struggles and

plights.