Protests Against the WTO: the Call for a Global Justice Movement

On

November 30, 1999, tens of thousands of people gathered on the streets of

Seattle, Washington in protest. Hundreds of organizations had planned months in

advance for this opportunity to speak out about their rights. Their grievances

were targeted at the World Trade Organization (WTO) and their unfair policies

toward humanity. These protests helped to spark a movement of global change, a

movement that strived to create a global civil society. The Seattle protests

against the World Trade Organization have been called the largest American civil

disturbance sparked by political issues since those of the Vietnam War era

(World Socialists 1999). They were an important accomplishment in recent

protesting and social movements. These protests will forever be remembered for

their impact on the world and the way people look at it.

On

November 30, 1999, tens of thousands of people gathered on the streets of

Seattle, Washington in protest. Hundreds of organizations had planned months in

advance for this opportunity to speak out about their rights. Their grievances

were targeted at the World Trade Organization (WTO) and their unfair policies

toward humanity. These protests helped to spark a movement of global change, a

movement that strived to create a global civil society. The Seattle protests

against the World Trade Organization have been called the largest American civil

disturbance sparked by political issues since those of the Vietnam War era

(World Socialists 1999). They were an important accomplishment in recent

protesting and social movements. These protests will forever be remembered for

their impact on the world and the way people look at it.

People gathered on the streets of Seattle with one common goal: to protest the WTO. The WTO was founded in 1995 and was created as an extension of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade or the GATT (Schott 2000). The purpose of the WTO was to help facilitate and conduct trade negotiations among the almost 150 member nations. However, many of the protesters of Seattle believed that it was “ an undemocratic, anti-labor and anti-environmental organization” (Taylor 2004). They thought that the WTO focused more on the interests of large corporations rather then those of the people and the environment. By doing so, this organization was restricting human rights, defying national sovereignty, and increasing global inequalities (Taylor 2004).

Specifically,

activists had grievances with many of the WTO’s polices and decisions. For

example, many people were angered by the WTO’s requirement of member nations

to maintain trade relations with all other members (Reed 2005). People believed

that this disallowed historical trade relations based on preferences, prior

agreements, and environmental aspects (Reed 2005). Also, protesters believed

that the WTO failed to create polices related to labor standards. The WTO had

vowed to uphold International Labor Organization standards but did nothing to

enforce them (Taylor 2004). At this particular World Trade Organization’s

ministerial conference in Seattle, trade ministers representing their countries

met to negotiate and discuss certain agreements and policies including the

Forest Products Agreements, Multilateral Agreements on Investments,

Biotechnology and Intellectual Property Rights (Taylor 2004). These issues in

particular attracted protest, but the fact that the social and environmental

concerns were not going to be addressed infuriated activists even more.

When

the WTO believes that a policy is violated by a member nation, cases are heard

by a panel of trade representatives. The nations involved must obey the

panel’s decisions even if it goes against a nation’s own domestic laws. This

policy of the WTO was a hot topic of protest because  many believed it undermined

national sovereignty and laws. Protesters focused on two cases in particular at

Seattle: the hormone beef and the shrimp turtle cases. In both of these cases,

the WTO ruled against countries that adopted regulations to protect public

health and the environment (Taylor 2004). The hormone beef case began when the

United States challenged the European Union ban on the sale of beef from cattle

fed artificial growth hormones (Reed 2005). The WTO, however, ruled that this

ban was an illegal barrier to trade and forced the European Union to open

markets to all beef, even though the Union opposed the use of these hormones

(Reed 2005). The shrimp and turtle case had a similar story. The WTO ruled

against the United States for banning shrimp from several Asian countries that

did not use proper turtle excluder devices in their shrimp nets (Taylor 2004).

This policy enforced by the U.S. reflected the country’s Endangered Species

Act. However, the WTO forced the

United States to abandon their policy or rewrite the law to meet the

organization’s standards (Taylor 2004). These

policies and decisions of the WTO motivated people from around the world to

protest.

many believed it undermined

national sovereignty and laws. Protesters focused on two cases in particular at

Seattle: the hormone beef and the shrimp turtle cases. In both of these cases,

the WTO ruled against countries that adopted regulations to protect public

health and the environment (Taylor 2004). The hormone beef case began when the

United States challenged the European Union ban on the sale of beef from cattle

fed artificial growth hormones (Reed 2005). The WTO, however, ruled that this

ban was an illegal barrier to trade and forced the European Union to open

markets to all beef, even though the Union opposed the use of these hormones

(Reed 2005). The shrimp and turtle case had a similar story. The WTO ruled

against the United States for banning shrimp from several Asian countries that

did not use proper turtle excluder devices in their shrimp nets (Taylor 2004).

This policy enforced by the U.S. reflected the country’s Endangered Species

Act. However, the WTO forced the

United States to abandon their policy or rewrite the law to meet the

organization’s standards (Taylor 2004). These

policies and decisions of the WTO motivated people from around the world to

protest.

Protesters

in Seattle had a greater goal in mind then just to fight against WTO policies;

activists sought to evoke change on a larger scale. They hoped to develop a

global civil society and help change the world as a whole for the better (Taylor

2004). The organizations and people that came to protest identified the WTO as a

legitimate target to ignite global transformation. The WTO was believed to be

responsible for many of the world’s grievances. However, bringing about change

would prove difficult as the problems and solutions ranged across nations and

peoples. In order to make an affect, protesters strove to create a “global

citizen identity” (Taylor 2004). This would help to link individuals and

nations from around the world together in one cause.

Creating

this identity and bringing people from around the world together proved to be no

easy task; however, it was not an accident. Organizations worked hard months in

advance in planning and organizing people to protest. More than 1,400

organizations from around the world identified themselves as opposed to the WTO.

Three US-based organizations became the primary architects for the Seattle

protests, including People for Fair Trade/Network Opposed to the WTO (PFT/NO!WTO),

AFL-CIO and labor unions, and the Direct Action Network (DAN) (Taylor 2004).

These organizations had different agendas in mind and mostly worked

independently. However they had a common goal and provided support for one

another.

The

PFT/NO!WTO was a branch of the Citizens of Trade Campaign (CTC) and were a

coalition of trade, labor, and environment groups (Taylor 2004). Through their

affiliation with the already established CTC, the PFT/NO!WTO had the resources

and man power for mobilization. The group soon opened their own office through

which they began to advertise, conduct educational events, and organize

protesters. This permanent post appealed to a politically mainstream audience

and gathered much needed support (Taylor 2004).

Organized

labor groups, led mostly by the AFL-CIO and King County Labor Council, also

began preparing for the Seattle protests (Taylor 2004). These groups had many

grievances with the WTO because of the damaged wage levels and living standards

caused by its policies. Their main focus was forcing the WTO to adopt standards

of the International Labor Organization. These groups used advertising through

memos, placards, and buttons to gather members to attend a mass march and rally

in Seattle. The AFL-CIO sent representatives to Seattle to help mobilize local

unions through workshops and seminars (Taylor 2004). The organization arranged

transportation to attract members from multiple cities, states, and countries.

Through their hard work, the AFL-CIO was able to organize the largest

group at the protests, an estimated 30,000 people (Hertel 2005).

of the International Labor Organization. These groups used advertising through

memos, placards, and buttons to gather members to attend a mass march and rally

in Seattle. The AFL-CIO sent representatives to Seattle to help mobilize local

unions through workshops and seminars (Taylor 2004). The organization arranged

transportation to attract members from multiple cities, states, and countries.

Through their hard work, the AFL-CIO was able to organize the largest

group at the protests, an estimated 30,000 people (Hertel 2005).

The

Direct Area Network or DAN was a group organized specifically for the Seattle

protests. DAN sought to coordinate a mass non-violent “direct action” aimed

at shutting down the WTO meeting at Seattle (Taylor 2004). This newly formed

group was backed by organizations such as the Global Exchange, The Rainforest

Action Network and the Ruckus Society (Taylor 2004).

These organizations helped to fund public workshops, training sessions,

and debates to gather support. The DAN organization set up a warehouse in

Seattle to provide food and shelter to protesters, as well as a place to hold

meetings, create props, and attend workshops (Taylor 2004). DAN was considered

the most radical of the three main groups, and was often isolated (Taylor 2004).

Despite

these organizations differences, they came together, along with hundreds of

other groups, on November 30, 1999 in Seattle.

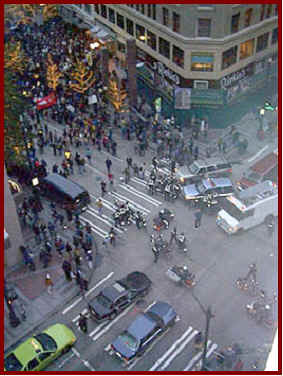

Tens of thousands, roughly 50,000, people gathered on the streets of

Seattle in protest of the WTO (Hertel 2005). Labor represented the largest

group; roughly two-thirds of the protesters were union members. (Taylor 2004).

To many, the scene that day seemed like circus, with many of the protesters

dressed in costumes while others sang, chanted, and rallied outside (Hertel

2005). Activists tried to change

the policies of the WTO while others tried to shut down the meeting altogether.

Activists held non-violent street protests, hosted rallies, and set-up

teach-ins to teach alternate perspectives on trade and globalization issues

(Hertel 2005). They practiced short-term blockades to limit access to the actual

meetings. They increased the noise levels so the delegates inside could hear

their grievances. Activists also worked within the meetings to have their voices

heard. Proposals of reform were created and entered negotiations through a

“back-door” strategy: some activists gained access to the meetings usually

through third-world countries’ delegates (Hertel 2005).

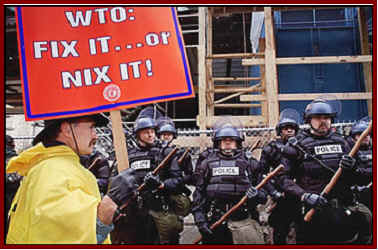

While

most of the activists performed non-violent forms of protest, a small group of anarchists engaged in violent acts such as

vandalism. The goal of these

anarchists was to halt the meetings in Seattle and destroy the WTO all together

(Hertel 2005). They sought to blockade the meeting in the most extreme manner,

which often included acts of violence. The Seattle police force took action

against these acts of aggression. However, the police were highly outnumbered

and were often blockaded by protesters, which made doing their job very

difficult. Once some of the protesters got out of control though,  the police

took more drastic measures including the use of pepper spray and rubber bullets

(Taylor 2004). These were mostly aimed at the violent protesters, but some

non-violent protests were victims of harsh police treatment that soon stirred up

controversy. City officials

declared a state of emergency in the late afternoon (Taylor 2004).

They soon designated downtown Seattle a “Protest-Free Zone,” but this

only inspired more protest (Taylor 2004).

the police

took more drastic measures including the use of pepper spray and rubber bullets

(Taylor 2004). These were mostly aimed at the violent protesters, but some

non-violent protests were victims of harsh police treatment that soon stirred up

controversy. City officials

declared a state of emergency in the late afternoon (Taylor 2004).

They soon designated downtown Seattle a “Protest-Free Zone,” but this

only inspired more protest (Taylor 2004).

The

media played an important role in the Seattle protests. Unfortunately the

minority of violent acts were the focus of much of the media during the Seattle

protests. The media criticized the police force actions, so much so that the

Seattle police chief retired shortly there after. Although the protesters

received some negative media coverage, the media also helped to bring public

attention to the issues of the activists. They forced the relationship between

trade and human rights into the spotlight (Hendershot 2004). The media helped to

spark ideas and discussions around the globe.

In

the end, the WTO ministerial meeting in Seattle collapsed due to disagreements

among the delegates and the mounting pressures from the protesters. Trade

negotiations failed and the meeting deteriorated. But, were these Seattle

protests a success or a failure? This often depended on the viewpoint of the

person, but many of the protesters thought the protests were a success. These

protests helped to launch a mass movement of global justice. It was a large leap

forward in public awareness of many of the issues brought out against the WTO.

The protests helped to build a foundation for change and they were a prime

example of diversity coming together in protest. This diversity and the sheer

numbers of these protests helped to connect issues globally and locally. The

protests had a “boomerang affect,” it gave smaller, less powerful nations

the opportunity and willingness to speak up against inequalities (Parrish

2004).

These

protests also had an impact on the WTO. They helped to open up debate where it

had not existed before. The protests put issues of economic policymaking onto to

the WTO agendas and into the minds of government and business leaders (Hertel

2005). They “woke up” the WTO, governments, media and the general public to

the discontent the activists fought against (Schott 2000). The WTO has made

efforts to open its dealings to the public and the press. Numerous documents are

now available online for public viewing and interpretation (Hertel 2005).

However, the policies and rulings of the WTO have yet to be formally

changed.

During the last seven years or so, protesters and

activists are trying to go from stirring up debate to making concrete changes.

Groups have formed to carry on the fight for justice. The Mobilizations for

Global Justice was one such group that was modeled off of the Seattle

mobilizations and protests (Parrish 2004). They helped to organize similar

educational workshops and continued to voice their opinions after the Seattle

protests. The Center of Concern, a faith based research organization in

Washington D.C., also continues to campaign against the inequalities of the WTO.

The Seattle protests have led to other protests including those at a

World Bank meeting in Washington D.C in 2000, the protests by the Free Trade

Area of the Americas in Quebec, and at the G8 Summit in Italy (Parrish

2004). However, due to the

increased security from the Seattle protests, large-scale protests are often

difficult.

During the last seven years or so, protesters and

activists are trying to go from stirring up debate to making concrete changes.

Groups have formed to carry on the fight for justice. The Mobilizations for

Global Justice was one such group that was modeled off of the Seattle

mobilizations and protests (Parrish 2004). They helped to organize similar

educational workshops and continued to voice their opinions after the Seattle

protests. The Center of Concern, a faith based research organization in

Washington D.C., also continues to campaign against the inequalities of the WTO.

The Seattle protests have led to other protests including those at a

World Bank meeting in Washington D.C in 2000, the protests by the Free Trade

Area of the Americas in Quebec, and at the G8 Summit in Italy (Parrish

2004). However, due to the

increased security from the Seattle protests, large-scale protests are often

difficult.

In some ways these protests can be considered a success, in others, a failure. One thing is for sure, though: these protests brought a large diverse group of people together with a common goal. Hundreds of groups and thousands of people spoke out against the World Trade Organization. The protests in Seattle brought up issues of trade, human rights, labor rights, national sovereignty, and global inequality. They helped to spark a movement of global justice. Although this movement is young and in its beginning stages, hopefully it will help change the world for the better.

Created By Michelle Manzi, 2006. The College Of New Jersey.

Works Cited and Additional Resources

All information not cited is thought to be public domain, if any problems with intellectual property arise,

please email me at manzi3@tcnj.edu