How a Diverse Group Banded Together Against the WTO

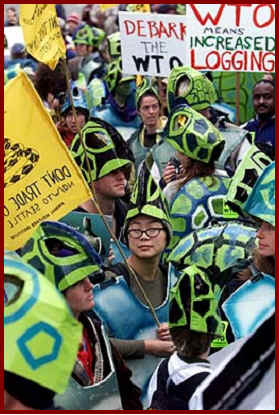

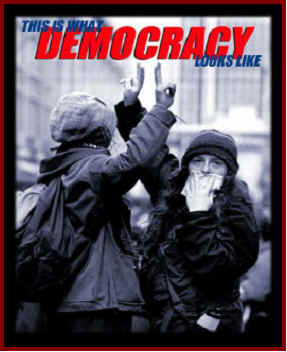

The people assembled in the streets of Seattle were labor unionists and

environmentalists, lumber workers and forest activists, students and teachers,

farmers and cheese makers, Germans and Ukrainians, Africans and Asians, North

Americans and Latin Americans, gays and straights, human rights activists and

animal right activists, indigenous people and white urban professionals,

children and elders. Some wore business suits, some overalls, some wore sea

turtle costumes, some leather and piercings, some wore almost nothing at all

(Reed 2005). A very diverse group

joined together in Seattle, Washington in November of 1999 to fight against the

World Trade Organization (WTO) and its unfair policies. Despite the differences

in nationality, race, religion, and ideals of the crowd in Seattle, tens of

thousands of people formed one united front in the fight for global equality.

Through a strong network of organizations, revolutionary technology, and

alternate media coverage, activists of the global justice movement banded

together through diversity to form one collective identity.

Although music was not an integral part of this movement, the creativity

that shined in Seattle, added to this already strong feeling of unity. Without

the ability of this diverse group of nations and peoples to gather on the

streets of Seattle, these revolutionary protests against the World Trade Organization

would not have made such an impact on the world today.

Seattle was not the first place that anti-globalization ideas were voiced, but

it was the first taste of how strong the forces against global imbalances really

were. This protest was the first place where the ideas of activists were brought

to the attention of the media and American public.

Seattle brought together hundreds of organizations and thousands of

peoples from around the world. It interlinked activists against the WTO

nationally and internationally. Seattle converged various related

anti-globalization movements into a united single movement. The movement gave

activist worldwide the sense that they were a part of something larger, a

movement instead of isolated issues. This brought activists to a new level of

self-awareness and confidence that others were fighting for the same cause that

they were. They were able to relate to one another and form a common bond, a

collective identity.

Organizations such as People for Fair Trade/Network

Opposed to the WTO, AFL-CIO and labor unions, and the Direct Action Network,

were vital in creating this collective identity (Taylor 2004). Hundreds of

organizations planned months in advance for these protests. Although these

groups mobilized largely separate constituencies, they shared information,

participated together in strategy meetings, and supported one another. In order

to have a strong movement, these groups had to work together or all would fail.

This network of groups strongly influenced the events in Seattle and became the

foundation of the global justice movement by defining its character and creating

opportunities for protests (Taylor 2004). Each

group had its own unique strengths, which were often complimentary to one

another. The groups indirectly helped out other groups in this network. This

interdependence of the groups made them cooperative and more willing to work

with one another. Thus an atmosphere with minimal conflict was created without

developing strong ongoing relationships (Taylor 2004).

This network of groups was crucial in organizing and motivating support for the

movement. These groups placed a strong emphasis on the way their messages to the

public were worded. For example, the labor organizations omitted suggestions for

specific concrete change and used nonspecific messages like that the WTO needed

to “reform” labor thus increasing th4e probability that it would have the

support of other interests. Through messages like these, the groups strove to

break down barriers of differences and appeal to all peoples. They translated

messages into terms that would be understandable and motivational. Groups tried

to word their messages in ways that would not provoke disagreement. The

months before the Seattle protests were spent informing the public and

encouraging them to join the fight. This network organized educational events to

educate the public about the WTO with speakers representing diverse interests

shared knowledge, experiences and proposed solutions to the audience (Taylor

2004). People are more likely to be motivated to  participate in collective

action if they believe that their effort will have an effect (Starr 2000). These

educational meetings informed people of the effects the protests would have and

motivated them to join. The meetings gave participants

many opportunities to

become acquainted and form ties to one another before the actual protests in

Seattle. These many different organizations were able to put their differences

aside and bring people from around the world together.

participate in collective

action if they believe that their effort will have an effect (Starr 2000). These

educational meetings informed people of the effects the protests would have and

motivated them to join. The meetings gave participants

many opportunities to

become acquainted and form ties to one another before the actual protests in

Seattle. These many different organizations were able to put their differences

aside and bring people from around the world together.

Along with these groups, the available media of today helped to spread the word of the protesters and unify activists from around the world. The Internet was the main proprietor in information sharing for the movement. The movement may not have been possible without the low-cost, quick communication and research possibilities of the Internet (Reed 2005). The Internet allowed groups to access hundreds of corporate and government documents that were helpful in understanding and strategizing against injustices. Through hundreds of websites, listservs, and personal emails traveling almost instantaneously around the globe, people were kept informed. Information could be translated into many languages breaking national barriers and uniting people on a global front. The Internet eliminated the need for face-to-face encounters but still kept up direct person-to-person contact.

This new media spurred a new kind of action as well, known as the “virtual sit-in” (Reed 2005). A group called the Electronic Hippies Collective organized this revolutionary event. This form of protest consisted of thousands of people visiting the official WTO web site. This would tie up its traffic as a traditional sit-in would. The group claimed to have mobilized more than a hundred thousand visits to the site on the first two days of the protests. This new form of virtual participation allowed people from all around the world to participate in the protests without actually being in Seattle. Another protest practice adopted with aid of the Internet was the creation of “shadow” sites (Starr 2000). These were fake websites that mimicked the design of the official WTO site with the protesters own content. Some shadow sites announced that the Seattle ministerial meeting was cancelled while others criticized the unfair policies of the WTO. This new practice was affective but often controversial since it often caused a cycle of disinformation.

On the days of the protests in Seattle, new media was also useful in forms such as laptops, camcorders, and cell phones. Cell phones in particular were helpful in keeping up communication ties. When police cut off the Direct Action Network’s communication systems, the group continued to update one another via cell phones. The cell phones were essential for coordinating blockades, informing protesters of police positions, and letting protesters know when reinforcements would arrive (Reed 2005).

Along with communication ties among

protesters, a group of alternate media organizations helped to keep

communication ties among the public. Independent media groups used existing

media of print, photography, video, and audio as well as an interactive website

where users could read, watch, and listen to stories as well as post their own

(Starr 2000). The website received over one million hits during the week of the

Seattle protests, more then CNN during the same time (Starr 2000). The media

group, known as Indymedia, set up nine live web cams overlooking the streets of

Seattle to capture protest activity. Thus these events were able to reach a

worldwide audience in little time. Up to the minute reports and photos were

available almost instantaneously to the public though laptop computers and palm

pilots in Seattle. A daily

half-hour video was produced and given to community access TV centers. A web

cast radio station, Studio X, gave live commentary and reports. Several

micro-power broadcast stations were used to reach all over the world by anyone

with Internet access. However, many people around the world did not have access

to the Internet and computers. Thus, Indymedia used the Internet to send audio

files and text files that were rebroadcast on local radio stations and printed

into flyers and newsletters so everyone could be informed. The information sent

around the world by these means connected activists in various nations to this

movement.

Along with communication ties among

protesters, a group of alternate media organizations helped to keep

communication ties among the public. Independent media groups used existing

media of print, photography, video, and audio as well as an interactive website

where users could read, watch, and listen to stories as well as post their own

(Starr 2000). The website received over one million hits during the week of the

Seattle protests, more then CNN during the same time (Starr 2000). The media

group, known as Indymedia, set up nine live web cams overlooking the streets of

Seattle to capture protest activity. Thus these events were able to reach a

worldwide audience in little time. Up to the minute reports and photos were

available almost instantaneously to the public though laptop computers and palm

pilots in Seattle. A daily

half-hour video was produced and given to community access TV centers. A web

cast radio station, Studio X, gave live commentary and reports. Several

micro-power broadcast stations were used to reach all over the world by anyone

with Internet access. However, many people around the world did not have access

to the Internet and computers. Thus, Indymedia used the Internet to send audio

files and text files that were rebroadcast on local radio stations and printed

into flyers and newsletters so everyone could be informed. The information sent

around the world by these means connected activists in various nations to this

movement.

The

media watched as back on the streets of Seattle, activists banded together in a

common cause. During the weeks prior to the protests, these activists had formed

a unique bond. Now, protesters were able to express this unity and creativity

through art and music in Seattle. Protest art groups such as Art and Revolution

helped in organizing artistic events of the day (Reed 2005). They set up

training to teach hands-on protesting tactics such as puppetry and street

theater. As the Direct Action Network handbook states, “Taking to the streets

with giant puppet theater, dance,, graffiti art, music, poetry and spontaneous

eruption of joy breaks through the numbing isolation…We must strive to use all

out skills in harmony to create an enduring symphony of resistance,” and

protesters did just that (Reed 2005).

Seattle was filled with artistic expression through sea turtle costumes,

dancing Santas, jugglers, stilt walkers, fire-eaters, clowns, thirty-foot tall

puppets, and cheerleaders chanting rhymes like “Ho, Ho, Ho the WTO’s got to

go!.” People hung banners with sarcastic attacks on globalization and the WTO

(Reed 2005).

The streets were filled with music through Mardi Gras style marching

bands, street parties, West African dances, and unique protest songs. One

example of musical expression was “The Rap Wagon,” which was a white van

with a powerful sound system blasting rap with titles such as “TKO the WTO”

(Starr 2000).

Many other artists also played their distinctive sounds through the use

of sound systems, C.D. players, the radio, and the Internet. People in the

streets were able to sing and dance along, creating a feeling of community.

These artistic and musical expressions were characterized as “festive

resistance.”

Unfortunately, these elements of music and art were not the main focus of

the activists. However, the creative edge of this festive resistance generated a

unifying bond for this diverse group.

Immediately

following the Seattle protests, virtually all the coalitions and groups involved

reported an upsurge of interest and activity

(Reed 2005). Still today, activists

continue to fight for the global justice movement. Many continue to work in

their particular corner of the world on issues most relevant to them. The

creation of the World Social Forum (WSF) was a key development for the movement

after the protests (Taylor 2004).

This group draws thousands of delegates from civil society organizations,

as well as tens of thousands of participant-observers every year for its annual

event. It has become the major counter-summit of the movement for global

justice. The WSF is a network of networks that come together to educate, access,

strategize and plan. This community of activists helps to keep the ties among

peoples strong which is vital in continuing the struggle against globalization.

This group draws thousands of delegates from civil society organizations,

as well as tens of thousands of participant-observers every year for its annual

event. It has become the major counter-summit of the movement for global

justice. The WSF is a network of networks that come together to educate, access,

strategize and plan. This community of activists helps to keep the ties among

peoples strong which is vital in continuing the struggle against globalization.

The Seattle protests changed the fight for global justice from a laundry list of issues and groups focused on the environment, genetically engineered foods, human rights, consumer protections, women’s rights, labor issues, poverty and dept relief into a coherent force focused on one enemy (Reed 2005). A highly diverse group of people gathered on the streets of Seattle to fight against global injustices. Through organizations and education meetings, they were brought together and informed of the movement’s goals and expectations. Revolutionary media, especially the Internet, connected people from around the world. This network of citizens, with varying ideas and backgrounds, were able to defy these differences and become a united front. They formed a collective identity as a group of people trying to overcome global injustice. Although music and art were not a central part of this movement, these creative elements built upon the protesters feeling of community. The bonds that formed that day are everlasting, as this movement carries on the fight of those who started it all on the streets of Seattle.

Created By Michelle Manzi, 2006. The College Of New Jersey.

Works Cited and Additional Resources

All information not cited is thought to be public domain, if any problems with intellectual property arise,

please email me at manzi3@tcnj.edu