Sussex

to Stonehenge: Nick Beykirch '00 and Patti McWhirr '00

Our

first stop, the Weald and Downland museum, provided a frame of reference

for understanding the steady pace of rural development that served

as a backdrop for the pageant of English history and politics. This

living history museum contains some forty buildings, several of

which date back to the 15th century. These buildings were rescued

from many regions of England, taken down, moved, and then set up

as they would have existed when they were first constructed. The

museum showcases agriculture and architecture, as well as domestic

life. Costumed craftsmen, farmers, and villagers periodically re-enact

events from country life true in every aspect to their eras, and

will answer questions posed by visitors as long as no references

are made beyond the time frame they represent. Our

first stop, the Weald and Downland museum, provided a frame of reference

for understanding the steady pace of rural development that served

as a backdrop for the pageant of English history and politics. This

living history museum contains some forty buildings, several of

which date back to the 15th century. These buildings were rescued

from many regions of England, taken down, moved, and then set up

as they would have existed when they were first constructed. The

museum showcases agriculture and architecture, as well as domestic

life. Costumed craftsmen, farmers, and villagers periodically re-enact

events from country life true in every aspect to their eras, and

will answer questions posed by visitors as long as no references

are made beyond the time frame they represent.

Our first night's stay was in a 12th century water mill in the city

of Winchester. Converted to a youth hostel, it proved to be our

most primitive accommodation. Low ceilings and shower-rationing

aside, sleeping in an 800-year-old building impressed everyone.

We also discovered that hostels are fertile ground for meeting other

foreign and British travelers.  Winchester's

cathedral, built in 1079 and the longest in all of Europe, was not

its first. The earlier church, established by King Cenwealh in 648,

was a much simpler Romanesque building. Either structure, but especially

the Gothic cathedral, would have required feats of engineering difficult

to envision in light of the limitations of power sources and modeling

techniques available. Winchester's

cathedral, built in 1079 and the longest in all of Europe, was not

its first. The earlier church, established by King Cenwealh in 648,

was a much simpler Romanesque building. Either structure, but especially

the Gothic cathedral, would have required feats of engineering difficult

to envision in light of the limitations of power sources and modeling

techniques available.

Many of the cathedrals in England contain a range of architectural

styles, mainly because their completion spanned so many decades.

Salisbury Cathedral, however, was built in a mere thirty-eight years

by three hundred men. Its Chapter House is home to the Magna Carta,

and its soaring spire, dating from 1313, is the tallest medieval

structure in the world. Nick summarized the experience saying, "These

two cathedrals left me with a new respect for the artifacts and

techniques of past centuries, many of which were the bases for technologies

we use today."

We left Winchester early to visit Salisbury, site of another famous

cathedral, and Stonehenge, whose antiquity is nearly beyond the

scope of an American imagination. |

Glastonbury,

Bath, and Ironbridge: Christina Hoey '99 and Ken LeCompte '00

Our

second day's travels brought us to the youth hostel outside the

village of Street, a suburb of Glastonbury. Glastonbury's abbey

ruin is its historical gem, with the well-preserved monastery kitchen

providing insight into medieval culinary technology. Our

second day's travels brought us to the youth hostel outside the

village of Street, a suburb of Glastonbury. Glastonbury's abbey

ruin is its historical gem, with the well-preserved monastery kitchen

providing insight into medieval culinary technology.

We recognized our high point in accommodations for the trip when

we approached Banwell Castle. This was the splurge of the trip,

though not expensive by American hotel standards. The country home

of a local squire, Banwell was built in Gothic revival style during

the 19th century, and its peacocks and four-poster beds delighted

our crew. It was the launching point for a thorough exploration

of nearby Bath, where a famous Roman spa was built on the site of

a long-revered natural hot spring. After the fall of Rome, Bath

declined until the 18th century, when it was rediscovered by  Georgian

society, whose architecture of honey-colored stone pervades the

city. Today the technology supporting the ancient Roman bath systems

is revealed and explained in detail at the Bath museums. Georgian

society, whose architecture of honey-colored stone pervades the

city. Today the technology supporting the ancient Roman bath systems

is revealed and explained in detail at the Bath museums.

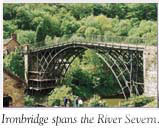

The next morning the group prepared for a transition into a more

recent era, and by early afternoon we had reached Ironbridge Gorge.

Here, through the exploitation of coal, limestone, iron ore, and

clay, the community of Coalbrookdale along the Severn River was

thrust into the Industrial Revolution. Coalbrookdale became the

birthplace of the world's first iron wheels, rails, and boats, and

the cast-iron bridge for which the town is named.

This technological center of the late 1800s was perhaps most vividly

portrayed at Blists Hill, a recreated Victorian town whose costumed

docents occupied the various stores and workshops and were glad

to explain and demonstrate their crafts. Mining and steam train

operation were showcased, and the Blists Hill bank allowed us to

exchange modern pence for locally minted Victorian shillings. And

as Christina noted, "One of the great qualities of a living history

museum like Blists Hill is its ability to inform visitors not only

of technological developments but also of the people who made these

developments happen." |

|