|

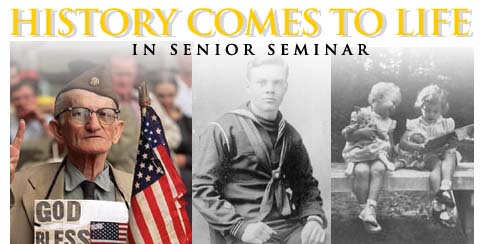

Like all students taking a history seminar last fall, Cynthia Paces’

class learned about the past. The only difference is that instead

of reading about it in books, her students got the story from living

persons.

It was all part of a new course in oral history taught by Paces.

Eleven students taking her senior seminar were required to interview

a person about a memorable aspect of his or her life that coincided

with an area of historical significance.

According to Paces, oral history became popular in the 1970s and

experienced a resurgence in the 1990s. Part of the reason Paces

likes the field so much is that, "Oral history gives people

a voice when they didn’t have one before. We can’t know

exactly what happened in the past. There’s not just one truth."

Students recorded their interviews with their subjects, verifying

and supporting their discoveries with extensive library research.

Paces said that like every other class, different students received

different things from the class.

"The seminar was a unique way of learning—delving into

a topic, doing research, and piecing it together," Maureen

Camphire ’00 said, "especially the personal interviews.

You can learn so much by listening to people."

Though Paces guided the students, she could not help them every

step of the way. She said that sometimes an interviewee would not

talk about an emotional issue or would get angry because of a certain

question.

"Everyone had something happen in the midst of this that was

troubling," Paces said. "You can’t always get people

to say what you want them to say.

"There’s a sense among some students that when you’re

writing a paper, you work real hard, but in the end, it’s really

only being written for one person—the professor. I wanted it

to last longer than that," said Paces.

Indeed, it has. All of the students’ reports are available

at the library, and Paces plans to begin a Web site this fall that

will archive the projects. Thumbing through the neatly bound copies

of the reports from last year, Paces said students became aware

of their interviewees in various ways. While one student spoke to

her grandmother, another student went all the way to Florida to

speak to a Jewish labor camp survivor.

One

of the reports, written by Christina Nightingale ’00,

was an interview with Harry Brockington, a Naval veteran of World

War I. Brockington has died since Nightingale interviewed him, but

she came to know him well during their talks. She even invited him

to her family’s Christmas dinner when she discovered he’d

be spending the day alone. One

of the reports, written by Christina Nightingale ’00,

was an interview with Harry Brockington, a Naval veteran of World

War I. Brockington has died since Nightingale interviewed him, but

she came to know him well during their talks. She even invited him

to her family’s Christmas dinner when she discovered he’d

be spending the day alone.

"He was the life of the party," Nightingale said. "Here

was a 100-year-old man who lived on his own, cooked on his own,

and still drove. It was really amazing."

Nightingale described her initial meeting with Brockington at his

Vincentown home as a memorable experience. "A few moments after

I knocked on the door, a thin, older man with winged-tipped glasses

and a Mr. Rogers outfit appeared behind the glass. I had to contain

my surprise to see such an energetic, mobile and talkative 99-year-old

man."

An excerpt from Nightingale’s report provides a glimpse into

the process of learning through oral history: Well, as far as we

could find out, Chris, there was a submarine U-151 that came from

Germany loaded with mines. She dumped mines off the East Coast here

all the way up to New York, up to Fire Island. I think they came

over in early 1918. They might have come over in 1917 when we entered

the war with Germany. I imagine the mines we set up were at least

20 miles off, where big ships go. They wanted the big ships to hit

the mines, not the small ones. The big ships were at least 20 miles

off shore when they were coming in or going out.

Mr. Brockington’s claim of the U-151 leaving mines off the

East Coast to target larger ships was substantiated by the work

of Henry J. James. Traveling at a depth of 35 meters, the U-151’s

main objective was to plant mines in two areas: off the entrance

to the Chesapeake Bay to catch ships leaving Baltimore and off the

Delaware to intercept ships outward bound from the Delaware Bay.

Yet in addition to all of the important historical information Brockington

shared with Nightingale, one comment that he made about his minesweeping

efforts will always stay with her. "What we were doing was

saving lives, not killing," Mr. Brockington told her. "I’m

proud to say that."

Brockington was determined to make it to his 100th birthday—and

did, but died just weeks later. Nightingale took Brockington’s

death very hard. Every morning, she said, he would lift up his bedroom

shade to let his neighbors know he was okay. But one day, the shade

stayed down, she said.

|

One

of the reports, written by Christina Nightingale ’00,

was an interview with Harry Brockington, a Naval veteran of World

War I. Brockington has died since Nightingale interviewed him, but

she came to know him well during their talks. She even invited him

to her family’s Christmas dinner when she discovered he’d

be spending the day alone.

One

of the reports, written by Christina Nightingale ’00,

was an interview with Harry Brockington, a Naval veteran of World

War I. Brockington has died since Nightingale interviewed him, but

she came to know him well during their talks. She even invited him

to her family’s Christmas dinner when she discovered he’d

be spending the day alone.