All About Fencing

Webster's Dictionary defines fencing simply as "the art or practice of attack and defense with the foil, epee, or saber."

We highly doubt Noah Webster ever fenced.

No, ask a fencer what it's all about, and he (or she!) will tell you it's about the hours spent in a cramped gym or underground studio hooked up to electric wires, advancing and retreating up and down a narrow strip, searching for the quickest and easiest way to land a touch on your opponent. It's about staring your opponent straight in the eye as you drive your foil straight into his gut. It's about the rapid succession of parry, repost, parry, repost, until your opponent, weary from the nonstop clinkety-clink of your weapons, lets down his guard for a split-second. And it's about that feeling you get when you seize that split-second to move in for the final touch and win the encounter.

The sport of fencing has been described by many as "physical chess;" an activity wherein the need for physical prowess and agility is rivalled only by the need for tactical thinking and reasoning skills. Each bout takes place on a narrow, rectangular strip called a piste. The piste is 14 meters long and 1.6 to 2 meters wide. En-garde lines for each fencer are 2 meters from the center of the piste, and warning areas are marked 1 meter from each end.

The History Of Fencing

Fencing has its roots in ancient combat. Around 1200 BC, the Egyptians began the custom of fencing for sport. Fencing, however, owes more to unarmoured dueling forms that evolved from the 16th century rapier combat. Rapiers were used for self-defense and dueling. Even though rapiers were edged weapons, the primary means of attack was the thrust.

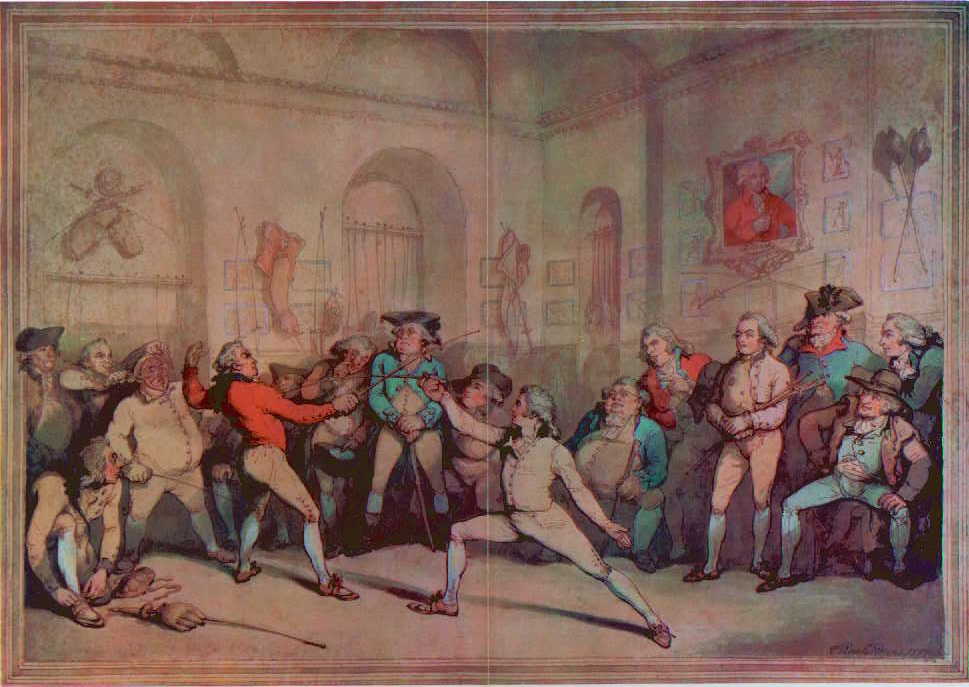

The Italians, Spanish, and French can all claim parentage for modern fencing. During the Renaissance throughout Europe the discipline of fencing took on the aura of high art, with masters refining and passing on to a select few their secret techniques. In the 18th century, treatises appeared in print setting forth the current system of rules and scoring, and prescribing a foil, a metal mask with eyeslit, and a protective jacket, or vest, as equipment for use. The rules were intended to simulate real combat while protecting the safety of the combatants. "Conventions" were subsequently adopted to limit the target area of the body and providing for a "right of way" for attacks.

"Right of way" was established to eliminate simulataneous attacks in foil and sabre fencing. It is the differentiation of offense and defense, made by the referee. Epee does not use right-of-way, but instead the fencer who first gains the touch earns the point. If both fencers hit within 1/25 of a second both earn a point.

Fencing has been in the Olympic program from 1896 onwards. The first Olympic games featured foil and sabre fencing for men only. Epee was introduced in 1900. Epee was electrified in 1936, foil in 1956, and sabre in 1988. Women's foil first contested in the 1924 Olympics. Women's epee contested in 1996 although it has been part of the World Championships since 1989. Women's sabre first made its appearance in the 1998 World Championships as a demonstration sport.

Choose Your Weapon...

Choose Your Weapon...

The sport of fencing is comprised of three weapons: the foil, the epee, and the saber. These weapons are usually connected to electronic scoring aids sewn into the fencer's garment. These aids are used to assist in the detection of touches. The rules governing these weapons are governed by the FIE (Federation Internationale d'Escrime). Here is a brief description of each weapon:

By the 18th century, the rapier evolved to a simpler, shorter, and lighter design that was popularized in France as the small sword. Although the small sword had an edge, it was only to discourage the opponent from grabbing the blade, and the weapon was used exlusively for thrusting. The light weight made a more complex and defensive style possible, so the French masters developed a school based on the defense with the sword, subtlety of movement, and complex attacks. The foil descended from this sword. The foil, weighing less than a pound, has a thin, flexible blade about 35 inches in length, with a square cross-section and a small bell guard. Touches are scored with the point on the torso of the opponent, including the groin and back.

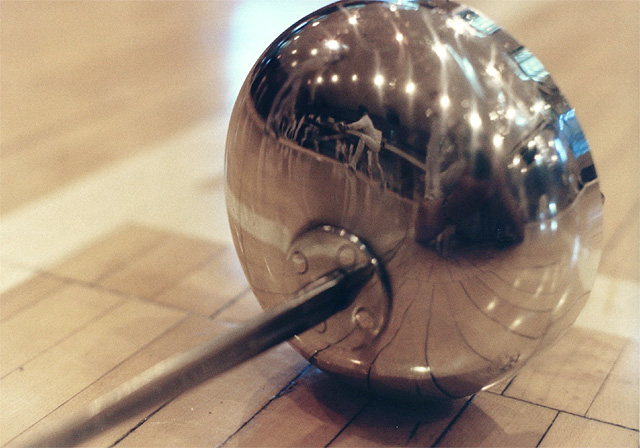

By the mid 19th century, dueling was in decline as a means of settling disputes because victory could lead to a jail term for assault of manslaughter. Emphasis shifted to defeating the opponent without necessarily killing him. Thus less fatal dueling forms evolved using the dueling sword, or epee de terrain, an unedged variant of the small sword. Later duels often ended with crippling thrusts to the arm or leg, and fewer legal difficulties for the participants. The epee is a descendant of this sword. Epees are similar in length to foils, but is heavier, weighing approximately 27 ounces, with stiff blades with a triangular cross-section and large bell guards (to protect the hand). Touches are scored with the point anywhere on the opponent's body. Unlike foil and saber, there are no rules of right-of-way to decide which attacks have precedence, and double hits are permitted.

Cutting swords had been used in bloodsports since at least as far back as the 17th century. Broadswords, sabres, and cutlasses were used extensively in military circles, especially by cavalry and naval personnel, and saw some dueling application is these circles as well. Italian masters formalized sabre fencing into a non-fatal sporting/training form with metal weapons (training previously being performed with wooden weapons). As with thrusting swords, the sabre evolved to lighter, less fatal deuling forms. Hungarian masters developed a new school of sabre fencing that emphasized finger control over arm strength. The sabre descended from these swords. It has a light, flat blade and a knuckle guard. It is similar in length and weight to the foil. Touches can be scored with either the point or the edge of the blade anywhere above the opponent's waist.

The target areas for each of these weapons are as follows: