Evolution and Classification of Viburnum

Phylogeny of Cannabaceae

Diversity of Figs

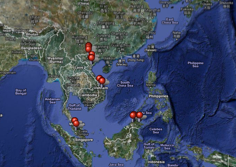

Viburnum (Dipsacales) is a group of ~170 species of woody plants that include many well-known ornamental shrubs. Viburnum occurs in temperate and subtropical montane forests across the globe with centers of diversity in temperate Asia and Central America. Our efforts to reconstruct the Viburnum phylogeny have suggested that this largely northern temperate group may have its evolutionary roots in the subtropical regions of Southeast Asia (Clement and Donoghue, IJPS 2011). We are continuing our efforts to collect Viburnum from around the world with recent expeditions to South America and Southeast Asia. These collections are being used to generate morphological and genetic data to expand the phylogeny of Viburnum and more accurately describe the diversity in this plant group. Led by Michael Donoghue and together with Patrick Sweeney and William Piel, we have received NSF support for our project, a “Cyber-enabled global monograph of Viburnum.” This grant will support fieldwork, morphological study and molecular work to study and resolve species complexes and prepare a global treatment for the reclassification of the group.

Our work on Viburnum involves a number of exciting collaborations exploring many aspects of Viburnum diversity. Erika Edwards’ lab at Brown University has been studying the morphology, anatomy, and physiology of Viburnum leaves while Marjorie Weber and Anurag Agrawal at Cornell University have been studying the interactions between mites and Viburnum mediated by the domatia and glands that grow on the leaf surface.

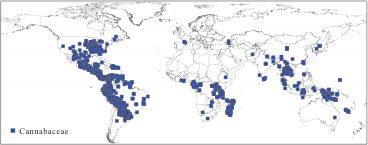

Although perhaps best known for its charismatic members, Cannabis (hemp) and Humulus (hops), Cannabaceae includes 11 genera and almost 100 species that are widely distributed in wet and dry habitats across the globe. Its most speciose genus, Celtis, or the hackberries, contains approximately 70 species and has been the focus of our study on the evolution and classification of the family. Further, hackberries have many biotic interactions that remain unexplored, such as being host to many Lepidoptera species including the Hackberry Emperor (Asterocampa celtis). With Eugenia Lo and Michael Donoghue, we are reconstructing a phylogeny representing all genera of the family using chloroplast and nuclear markers. This phylogeny will serve as the basis for further work to more accurately describe the historical biogeography associated with the diversification and distribution of hackberries, and set the stage for future ecological research concerning its biotic interactions with other organisms.

One of the more puzzling questions for an evolutionary biologist to ask is why some lineages are very species-rich while others are not. Comparing sister lineages can help identify characteristics, including ecological and life history traits, that correlate to changes in the rate of diversification. The sister relationship between figs (800 species) and the tribe Castilleae (Moraceae; 60 species) offers a unique system to use a comparative approach to study the patterns and processes that underlie shifts in diversification rates. In collaboration with Nina Rønsted at the Natural History Museum of Denmark and George Weiblen at the University of Minnesota, we are using the newly expanded phylogeny of Moraceae to test the long-standing hypothesis that the evolution of the fig is correlated with a significant shift in diversification, as well as identify other groups of Moraceae species that have undergone accelerated rates of speciation. We will then utilize the extensive morphological data available to identify changes that correlate to these shifts to look for general trends and propose hypotheses to explain these findings for further study.

Research Interests

Office - 117 Biology Building

Lab - 236 Biology Building

Phone - 609.771.2672

Email - clementw at tcnj.edu

Viburnum

Celtis

Pteroceltis

Ficus

Antiaropsis

Distribution of Cannabaceae

Viburnum coriaceum from Malaysia. Photos courtesy of P.W. Sweeney.